Extra Ecclesiam nulla salus

(Outside of the Church there is no Salvation)

In order for strategies to become more permanently established they need to be theorised.

Just as the Anarchists theorised the workers councils as the vehicle of liberation, Kautsky and the Marxist Centre theorised the mass socialist-labour organisations as the agents of socialist transformation.

The view was brought out in the debates between Otto Bauer and Kautsky over the USSR in the 1920s and 1930s. Bauer argued that there could be a Russian road to socialism; that the backward conditions found there facilitated the crash-course of industrialisation which would pave the way for socialism in the future.

Emancipation through Organisation

For Kautsky this was illusion. Socialism does not arise from industrialisation per se. It comes from the action of the working class, action which can only occur via their own free, independent organisations. And it was precisely these which were absent in the USSR, with only one legal political party, trade unions which were under its tutelage, and a pervasive political police.

For sure, a technically advanced country was the precondition for the very possibility of an urban working class, never mind a working class organised into its own institutions. Before capitalism the masses existed in a permanent state of subordination broken only by sporadic and doomed uprisings, inherently incapable of instituting a socialist mode of production.

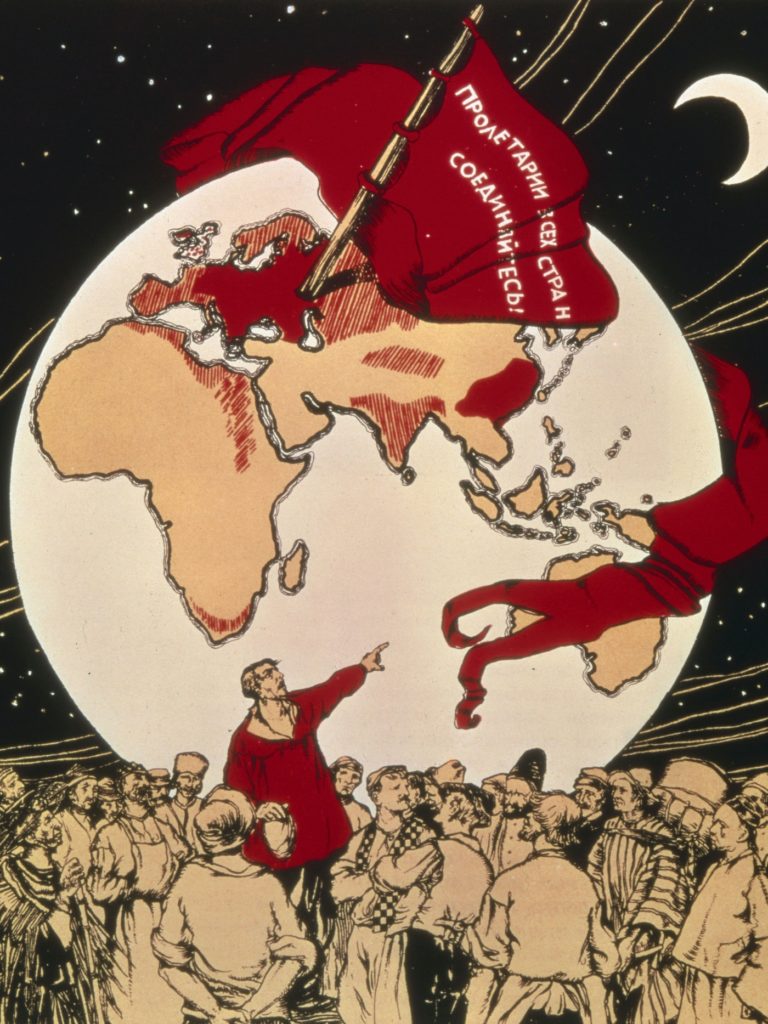

The creation, through the expansion of capitalist production, of the urban working class provoked a new and qualitatively different round of the class struggle: not, this time, between the bourgeoisie and the aristocracy, but between capitalism’s creation, the modern proletariat, and the capitalist class itself. And it was the class struggle that arose from capitalist industrialisation that forced the working class to organise its own trade unions, its own co-operatives, and, eventually, its own political party. It was to be through these institutions — so went the narrative of Second International Marxism — that the working class would build such hegemonic influence that it could win state power and transform society by transforming the mode of production.

If a large political party is a prerequisite for gaining control of the state, large worker organisations are also a precondition of socialism. Without organisation, the working class is just an amorphous mass of individuals, at the mercy of capitalist command of resources and its torrents of propaganda. It is only through organisation that it becomes an active player. And without organisations we cannot organise labour on a mass basis. If the First International’s famous slogan proclaimed that the emancipation of the workers would the be the task of the workers themselves, the Second International’s variation amounted to “the emancipation of the workers is the task of the workers’ organisations”. Not as pithy, but more specific.

In the absence of mass socialist-labour institutions workers’ capacity for action is restricted to protest and destruction. Kautsky, in the debates with Luxemburg, was explicit about the limitations of unorganised mass actions, i.e. spontaneous actions that were not co-ordinated by specific institutions. These type of action are restricted, they’re only defensive or destructive political actions, i.e. they could bring down a regime (as they did in February 1917) but they could not in themselves construct an alternative to the existing order except through the workers’ own political party and, critically for the project of raising a socialist mode of production to dominance, via co-ops and labour unions. Spontaneous action was by no means rendered redundant by the rise of the labour organisations; under certain conditions, essentially extremely repressive conditions such as existed in Tsarist Russia, or indeed in the final toppling of the Kaiser, it played an indispensable role. It also served to act as a reserve weapon against the capitalist class should it force the labour movement into a smaller and smaller space of legal existence.

But to go beyond the mere destruction of a conservative force, the organisations needed to exist and to exist on a mass scale while being imbued with a socialist, and preferably Marxist, ideology. To be sure, socialists could not bring about the revolution at will. There were much larger social forces at play: the erosion by industrialisation of the feudal remnants; geo-political manoeuvring; the pace of technological developments, etc. But socialists could control what they did with their own organisations. They could choose to pursue a purist revolutionary line and dispense with the mass worker organisations or they could choose to focus on direct economic action, as advocated by the syndicalists. In Kautsky’s view, they needed to prioritise the building of their own organisations and wait for the dynamics of capitalist development to deliver opportunities for winning power, an approach he called “the strategy of attrition”.

Contra Pannekoek, who viewed the strategy of attrition as in effect a form of “actionless waiting”, it was not going to be a passive affair. It involved a continuous strengthening of the movement institutions: more recruitment into the labour unions and strengthening their capacity for struggle; more and larger co-ops; increasing the membership and popularity of the party and its related cultural clubs; deepening the socialist intellectuals’ understanding of economics, the materialist conception of history, and expanding the reach of the socialist publications, etc. In sum, it involved the construction and continual expansion of a socialist ecosystem of organisations which could withstand the considerable pressure brought to bear by their capitalist and aristocratic opponents. Hence the title, the strategy of attrition.

Having outlined, nay bludgeoned, the importance of socialist organisations we are in a position to identify the role of electoralism. On their own, elections don’t put us on the road to socialism; they just do what the Trotskyists always accuse the Marxist minimum programme of doing: of making capitalism more tolerable — an under-appreciated virtue to be sure, but in any case a different one to what we are trying to achieve. It is only as a component part of the strategy of attrition that electoralism plays a critical part in moving beyond capitalism. Winning power is therefore not the only goal of electoralism; every bit as important is the role it plays in building a mass socialist party capable of winning it and of controlling the apparatus when it gets there.

For the supporters of council (soviet) democracy and the vanguard insurrectionary party, this is an entirely redundant approach. If anything the creation of permanent mass institutions becomes a fetter which prevents a revolutionary overthrow of capitalism by the treacherous actions of its bureaucratised leadership when the hour strikes. But for the Marxist Centre, as the proponents of the attrition strategy were known, the task of building up the organisations is the heart of all socialist activity. Not only should elections be seen in this light, but so too should demonstrations, leaflets, pickets, participating in single-issue campaigns and basically everything else we do.

Pannekoek and Luxemburg misjudged two factors. They overestimated the ease with which radical or direct action could escalate into revolution and they underestimated the importance of building the mass socialist-labour organisations. In a way this was understandable. Very significant gains, especially in the extension of suffrage, were being made in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution and, secondly, they had come to political maturity in an environment in which mass socialist organisations were a feature of social life. They were taken for granted. The issue, from their perspective, was to set these organisations in motion. But from our perspective, a century later, and having witnessed the eclipse of all varieties of socialist parties in the advanced capitalist states, it is the absence or severe weakness of mass organisations that is the problem, not that they are too conservative. Recreating them is not a trivial problem. There are no shortage of Luxemburgist alternatives, i.e. radical attempts at street demonstrations, from the anti-WTO protests of Seattle to the Occupy movement of 2011. But they have proved to be no panacea and when capitalism tottered in September 2008 there wasn’t the slightest question that there was an alternative economic system that could step in and immediately take over. The strategy of attrition, of building up the mass socialist-labour institutions, is designed to solve that problem.

Eco-system resilience and virtuous cycles / cumulative growth

The emphasis on the long-term building of mass organisations carries with it a number of key benefits. Take media, which are indispensable if we are to compete with capitalism for ideological dominance since that is how public communication to vast numbers of people occurs. We need funds to organise media, not just newspapers but television stations, websites, iPhone apps and the like. It costs money to pay journalists, sub-editors, programmers, and designers. We lack the capital but we have the numbers, an advantage that is only realised when we are organised. The potential volume of small contributions is immense and while it may not match what is available to the capitalists, it would certainly enable us to promote a socialist worldview at a mass level and enter in serious competition with the ruling class.

The German Social Democratic party had a myriad of social clubs: it had its own media apparatus, selling a million copies a week and with many more readers. It had theoretical journals, but it also had summer camps, athletic clubs, cycling clubs, even smoking clubs. The Italian Communists existed at a similar level. What they had in effect was an entire eco-system of organisations.

These don’t necessarily lead to radicalism, but they do lead to the organisations planting deep, deep roots in society. In many ways, they created something that is closer to a secular church than to a mere political party, and they reaped the benefit of the emotional attachment that their members had for the movement so that even a prolonged period of fascist reaction could not uproot them from society.

Once socialist institutions reach a critical mass a positive feedback loop kicks in. Our media normalises the idea of a co-operative economy, which leads to passive support, more donations, more votes, and more activists which leads to an increase in services: new worker co-ops, mutual aid funds, social clubs, choirs and so on. These further project the viability of socialism as a movement and an ideology which leads to further support, more donations, the surplus from the co-ops going to fund the party, which promotes the general idea of socialism through its increasing resources and so on in a positive feedback loop. A process of ratcheting up is underway, leading to a virtuous cycle in which cumulative gains are now possible.

In contrast, insurrectionary political parties are not at all oriented to working that way. Their primary strategic approach is to engage in federalist political coalitions (sometimes over-theorised as a united front) or, more commonly, single-issue campaigns in loose alliances with other far left groups and assorted independents. Whatever the obligation to engage in single-issues campaigns — and they are just a fact of political life — these campaigns rarely get beyond that particular issue itself. So, when that campaign is over, irrespective of whether it has ended in victory or defeat, the next campaign must start from the same low basis, lacking internal infrastructure and the political equivalent of brand awareness. The co-ordinating mechanisms must be constructed from scratch. As a single-issue campaign, it must stick fairly closely to the issue at hand or risk alienating the non-political people who are just concerned about it and not the wider political situation.

But there is no cumulative benefit because the organisations are different. The supporters who engage with the issue of unfair tax might have very little interest in an oil pipeline in Alaska. In order to benefit from the cumulative process of individual campaigns, there needs to be continuity of organisation so that when the next issue comes up, we are starting from a more advanced point.

The insurrectionary strategy fails badly at this and in fact revolutionary parties are not set up to take advantage of the often trojan work they do behind the scenes in these campaigns because they don’t want to build mass non-revolutionary parties. So, for them, it’s not even a major problem as their strategy relies on an outbreak of revolutionary upheaval rather than incremental growth of organisations as the vehicle of social transformation.

Unfortunately, it’s simply not possible to get big and capable institutions in one go. Even in highly favourable circumstances, there has to be a pre-existing institution that is set up to take advantage of it, which takes time to get its internal organisational structure and external strategy into presentable shape. It is necessary, therefore, to adopt a strategy that enables cumulative growth and that entails, by definition, having institutions which persist through time. But in the vanguard model the most long-lasting organisation is the revolutionary party which is precisely the one that is least able to grow to a considerable size. It is only the ephemeral single-issue campaigns and ideologically fluffy alliances which are able to achieve major proportions and they, because of what they are, are structurally incapable of persisting through time, thereby preventing any possibility of cumulative growth. As long, therefore, as the radical left maintains its current division between revolutionary and mass organisations it will be incapable of ever attaining the strength to implement its programme of socialisation.

In contrast, the classical Marxist approach of merging the socialist intelligentsia with the mass labour movement to form a socialist-labour movement provides a way out of the inability to either never grow large enough or for the mass organisations to be bereft of a socialist ideology. This “merger formula” is the conception that undergirds the strategy of attrition just as theory of the vanguard party fits snugly into a strategy of insurrection.

Political Consequences

Electoralism is the most important political activity in the European and North American societies and in practice it forms the centrepiece of activity for the remaining mass socialist-labour parties, such as Syriza in Greece, the French Communists and so on. Although putting the party and its programme to the test in elections is the priority it doesn’t preclude a host of other activities, including involvement in single-issue campaigns. In practice these will take up a lot of time just as they do now for the radical left. But in order to benefit from electoral work there has to be an institutionalisation of the gains, whether through increased participation in the party or union, more subscriptions to sympathetic left-wing media, joining a co-op or simply voting for the party come election time. These and other possible methods of harvesting the labour expended in the springtime of campaigning all depend on having institutions capable of soaking up the goodwill.

Organisation enables a sort of alchemy; the transmutation of goodwill into support and practical activity over the long term. Mass parties (and associated organs, co-ops, etc.) are not just admirably suited to achieving this, they are absolutely necessary. For every cadre member who joins a revolutionary party, there will be thousands more who are sympathetic to the basic goals of socialism. An emphasis on the destructive side of socialism, i.e. one which focuses on the necessity to smash the state, makes it harder for these potential sympathisers to participate in the movement in a sustained, long-term way, if only because of its intrinsic lack of plausibility. And even where single-issue campaigns are necessary, which seems likely to be the case for a long time to come, a socialist electoral party has no need to hide its politics in the initial period and then rush to spray them all over the campaign when it looks like it’s coming to an end.

The strategy of attrition is, therefore, compatible with a type of politics that is close to where many people already are. Its radicalism lies in its goals, not in its practice and this makes it easier to interact with non-socialists on an open basis. There is no need to hide its insurrectionary orientation because it doesn’t have one. As long as the party has a programmatic commitment to a co-operative mode of production and uses other avenues, e.g. its media or its public representatives, to articulate that, its mere presence as an ally of campaigns is enough to raise awareness of its goals.

In political terms, it requires genuinely engaging in electoral politics with the aim of winning since that is both the route to democratically gaining power and the best way of achieving large size in the political realm. It’s often argued that engagement with electoralism detracts from the core message of promoting socialism, as more immediate concerns, including the need to get re-elected, crowd out the longer term vision. This is a valid insight, but the assumption that ignoring the immediate ways people interact with politics doesn’t solve it. It just results in even less opportunity to engage with folks about any sort of politics at all.

For sure, at the micro level, the focus on the day-to-day is inevitable. It is, however worth taking a broad and long, i.e. decades long, view of its function. People aren’t going to be won over to socialism from a few chats at a door or a round of public talks. Shifting people’s values, consciousness, and tribal loyalties is a complex process. But each interaction can be a contribution to a movement gaining credibility. Every iteration of positive, even neutral contact between socialists and Joe Public chips away at the negative assumptions inculcated by the wider culture. But, more than that, electoral participation and victory conveys the impression of a competent organisation and as low-level messages for socialism seep through, the idea becomes normalised. Electoral validation helps create a culture where socialism can be discussed.

Now, for micro-interactions to be a contribution, they have to be a contribution to something. And something with an ability to scale. Promulgating revolutionary insurrection, smashing the state, etc., does not at all mix with chatting to Mary about the cut to child benefit. On the other hand, where there is a pre-existing movement that projects a grander vision, then each iteration of micro-contact about non-revolutionary issues serves to normalise that movement and therefore its vision. Clearly there is a danger that the day-to-day concerns force the grand vision into the background. Such is the risk of engaging with reality. But without being able to relate the day-to-day with the longterm project, the proponents of socialism will remain very isolated intellectuals.

The more that our activists can make the connection between the two the better, but as anyone who has had experience knows, it’s damn hard to get up in a workplace staff meeting about overcrowding in the canteen and make the connection with global capitalism. The same applies for potholes on country roads or traffic calming measures in the city centre. Occasionally a gap will open and the activist can make a punt about generalising the inadequacies to the economic system itself, but usually it will make you look a bit strange, especially if that opening is forced, in which case it can actually be counter-productive (which is one reason why those American Spartacists come across as really bizarre in many of their public interventions).

The task of promoting socialism — the collectivisation of the economy, co-operatives, etc. — will be made much easier for the grassroots activists the more that our intellectuals and prominent party members (MPs, etc.) can articulate it in a defensible manner. The starting point for this cannot be the mass media, which confines you to soundbites or at most a critique bereft of the opportunity of addressing structural issues, such as the ownership of the means of production. To even utter the phrase “the means of production” would probably take up half your response time on pretty much all mainstream current affairs programmes.

That battle takes place at a different level and the MPs get a simplified message, e.g. democratic control of investment, promotion of co-ops. Even then, most of their opportunities for interaction with the public will be on non-socialist issues, corruption, waste, war, civil rights (including gender equality, solidarity with immigrants, etc.). Every time they do well on these issues they increase the probability that the economic message is taken seriously. The more that happens, the easier it is for the grassroots activists to do the leg-work because the socialist vision is animating the movement as a whole. Thus, whatever strengthens the party / movement strengthens socialism, providing of course, the party continues to place socialisation at the heart of the project.

The Costs of the Strategy of Attrition

But if the merger formula is vastly more likely to lead to success, it far from guarantees it. Although it solves the problem of never being able to get on a track of cumulative growth it does run into the very heavy problem of integration into the existing political-economic system. The fate of the German SPD and the Italian Communists is ample evidence of the seriousness of the problem. All actions have costs and the cost of a mass organisation is a bureaucracy without which it cannot be maintained for more than a few months — not long enough to get the cumulative growth we need. When radical left groups are small they can persuade themselves that a distinct apparatus is unnecessary because for them it more or less is unnecessary. But that doesn’t apply to groups with millions of members, which is the scale we need to be aiming for.

Bureaucracies may be necessary, but they are also dangerous as they have a tendency to escape the control of the membership. Their first duty is to preserve the organisation itself and this leads to a conservative mentality. Again, this is unavoidable if the organisation is to exist. A trade union which hurled its members onto the barricades at every opportunity would soon see itself reduced to a fringe group.

In addition to the natural tendency towards conservatism, mass organisations of socialist opposition will come under immense cultural pressure. Its members will be subject to pro-capitalist propaganda and won’t be immune to the effects of the wider culture, which is massively suffused with capitalist values. Indeed, if socialists provided no other service than creating media capable of competing with the propaganda machines of the right, they would render an immense service to humanity.

The pressure of the wider pro-capitalist culture combined with the tendency towards increasing conservative apparatus makes the strategy of attrition a risky one. There is a race on between the socialist organisations aiming to transform capitalist society before capitalist society transforms them. The calculation is that the socialist-labour institutions can last long enough and make socialism an attractive enough ideology so that when the cracks appear in the capitalist edifice, they will be able to sweep in and begin restructuring the economy. But there is no question that the strategy of attrition courts integration if those cracks are patched up quickly enough. If the capitalist mode of production proves to be healthy over the long-term then it is likely these organisations will suffer the fate of the SPD or the PCI. But it puts us in the game; a game we might lose, but also one that we might win. Without the mass organisations the insurrectionary groups aren’t even in the competition and so while they can’t ever lose, they can’t ever win either.

Socialists have an important role in the struggle against the domination of the apparatus of the movement itself. The battle for socialism must be won not only in wider society, but within the socialist party and within the co-operatives and trade unions, not just once, but year after year until socialism is the dominant mode of production. Encouraging the participation of the grassroots in the life of the party is also an essential feature in keeping the bureaucracy in its box. In recent years, a lot of thought has gone into new forms of democracy, e.g. liquid democracy, sociocracy, sortition, etc. While these are worth experimenting with, the chief weapons remain freedom to organise and the freedom to articulate criticism and dissent. Compared to them, the precise procedures that are used fade into second place. This freedom requires a party tolerant of diverse views and one that facilitates their expression through its own institutions, e.g. magazines, summer schools and the like. Provided the dissenters do not have an agenda of splitting the mass party, the dissent is likely to strengthen rather than weaken it.

Further, the existence of a wider eco-system of organisations promotes alternative material interests to that of the status quo. A leadership whose resources depend on funding from a vibrant co-operative or union movement will be constrained from throwing their lot in with capital.

Forms of Democracy

As this piece is centred on immediate strategy, it has focussed on the two main choices: a vanguard party or a mass party. But as we saw, there is a second part to the insurrectionary equation and that is the mass assemblies, which are usually held up as a superior form of democracy to the ‘bourgeois’ form of the parliamentary systems.

There are many varieties of both systems, but the main differentiating feature lies in the conception of the role of the party as a mediating force or promoting the direct participation in the decision making process. That is, in current democratic systems, we vote for representatives who pass laws according to the strength of the party to which they belong. The criticism levelled at this type of system is that the representatives escape the control of the electors. The alternative is based on some form of assembly democracy in which the masses can participate directly. These federate and elect delegates to co-ordinating assemblies and if they cover a large enough territory these secondary councils do the same again, thereby forming a nested pyramid structure, all supported by the base assemblies. There are lots of problems with such a complicated system as is evidenced by the rarity in which they have been capable of supporting mass institutions, let alone being the basis of any state. Even at their height in the Russian Revolution, the assemblies (or soviets) only managed to exert significant social power for about 12 to 15 months.

As is often the case, the cure of assemblies is worse than the disease of partyism. Whereas partyism accepts that differences of opinion are based on real material interests, the assembly form, especially when it uses a form of consensus decision making, assumes the fundamental identity of interest amongst all the participants. The hostility to parties makes sense for proponents of the council form if differences of opinion are based on ignorance or bad faith. And that assumption is warranted in certain conditions: in sects such as the Quakers in which the membership do have, more or less, the same worldview and the same belief in the power of supernatural inspiration it is quite workable.

In politics, however, life is more complicated. Getting past capitalism is an incredibly difficult problem to which there are often no obvious solutions. At the outbreak of mass protest or revolution this is not a problem since the issue presents itself to the opposition in a simple way, e.g. “down with the regime”, “against the 1%”, “they all must go” (Argentina 2001). Sooner or later, however, it becomes necessary to move beyond a simple formulation of the problem and to advance structural solutions. This is hard for a number reasons, not least the number of variables that have to be taken into consideration. Because of that it becomes difficult to predict the consequences of any given policy.

For instance, given the looming problem of climate change, should we develop an energy infrastructure based around nuclear power instead of wind and solar power? Nuclear could solve the energy problem once and for all, but it could also lead to a loss of social cohesion if it is unpopular due to safety concerns. Wind and Solar might not be able to solve the looming climate change problem given the relatively paltry power generation capabilities they have, but perhaps if they were made the keystone of our climate strategy, investment would flow to research and development which would lead to them catching up with nuclear. Society has only a limited capacity to invest in energy infrastructure so it has to make a choice between them. Even experts do not have a consensus around it for the simple reason it’s a tricky problem.

It is hard to predict the consequences of any given policy but the difficulty escalates exponentially when we attempt to understand the the consequences of the consequences. It’s not that nobody is thinking about it, it’s just that the only problems we can solve are the ones presented to us by the environment and since we have yet to trigger the process by implementing the first tier of solutions we have yet to be confronted by the altered environmental conditions to which they give rise, thereby making it hard to assess what issues will give rise to the new set of problems. Consciousness and science help for sure, but they do not remove this issue of ‘future blindness’.

This problem is a fundamental one and has nothing to do with direct democracy or capitalism or even human nature.

And the energy problem is a fairly simple one to solve compared to the figuring out the likely issues arising out of socialising the means of production, taking control of investment and progressively reducing co-ordination of production via the market. Inevitably there will be different views on these issues in a way that there simply isn’t regarding incontrovertible facts (the earth revolves on its axis; the Irish are drunken peasants).

We can only rely on the collective will of society as expressed, after prolonged discussion, by the majority. Irrespective of the procedural form of democracy we choose, people will come together to form coalitions around the major issues of the day as they are too important to not try and win a majority for one’s own position. These coalitions will coalesce as people of similar values and intellectual orientation will find it easier to compromise with each other and form a stable alliance. This will give that group an advantage in its struggle with other coalitions as they will be better able to mobilise more support more often to back up its position. If the other coalitions are to stand a chance of having their views listened to, they will have to similarly form a stable enough formation that can garner a competitive level of support. In other words there will be a selective pressure for unity and the ability to be permanently aligned. And with the inevitable emergence of such tendencies we are right back at, in effect, a party system.

The absence of a systemic tolerance and utilization of tendencies (or factions or parties) does not result there being no distinct factions at all. This is impossible since they reflect real differences in society. It just means that the dominant faction is the only one that is organised as such and this gives them a permanent advantage in the competition with other tendencies. If socialists refuse to organise its own organisations in a way that can outcompete the pro-capitalist parties, they will simply be swept away no matter how directly democratic the procedures are.

The assumption of underlying consensus is not just a mistake of the modern day radicals, inspired by Occupy or the 1960s New Left. Lenin, in The State and Revolution, consistently treats the working class, indeed the revolutionary population in general, as being of a unified mind. There is zero indication that he expects there to be a continual democratic struggle between tendencies for supremacy. One of the rare mentions of such a possibility is his offer prior to the October Revolution to be a sort of loyal opposition to the SRs and Mensheviks if the latter would take power via the soviets. But after that there is vanishingly little. The assumption that the councils would be of one mind and that that mind had vested the revolution to the Bolshevik Party led to, at first, intolerance of opposition — even socialist opposition — but eventually to outright repression of every organisational manifestation of opposition to the Bolshevik government.

But being of one mind is vastly unlikely when we are confronted with important issues and afflicted by future blindness. What if one tendency wants to pay compensation to the capitalists and another wants to expropriate them outright? Either the minorities can be expelled as occurred in the French and Russian Revolutions or the various tendencies can coalesce into parties, which strive to attain a majority.

If the expulsion route is followed, a major civil war is inevitable, not just between the right and the left, but within the left. The experiences of the Russian and Spanish Revolution indicates that this is a real possibility and progress to socialism will be delayed for a long time to come. Political differences are best fought out politically, in the open, and via democracy.

1917 Russian Assembly Election

If there is to be democracy there will have to be periodic election to the assemblies. Those of a similar worldview will create organisations and strive to win a majority within the councils, which is what happened in Russia and everywhere else the council form broke out. If political parties are allowed, then we are essentially in the same position that we are now, albeit with a much more decentralised system, which if anything is vastly inferior for advancing towards a collectively run economy. And it is hardly worth the effort to stage an insurrection so that we can have elections to representative bodies which are dominated by political parties, when that is pretty much what we have already. 1

Worse, the promotion of the council system goes hand-in-hand with a profoundly anti-political mindset that we see in the downplaying of the role of political parties. We see this in things like the Irish Occupy stuff of a couple years back where they’d object to political party banners on their demonstrations or asking members of political parties to participate in a personal capacity only. Again, Lenin, in his weird moment of anarchism when writing State and Revolution, captures that mentality: the soviets are conceptualised as organs in which the decisions that workers have to make are administrative ones; they is no hint that there will be political decisions to be made. And with no politics, there is no need for multiple political parties.

In fact, from our point of view, we want politics to be conducted along party lines because we want there to a be an openly socialist party with the aim of a co-operative mode of production. We want people to choose socialism and to know that they are choosing socialism, which is only possible if there are other parties espousing a different goal or even just a different route. We don’t want them to fall into radicalism through engagement with street demonstrations that have snowballed into insurrection because they’ll fall out of that radicalism just as quickly. Rather, an explicit choice to vote for and/or to become an active participant in the socialist movement is a much better indication of support for the socialisation project.

Mass participation is, of course, a vital feature of any real democratic system, let alone a socialist one. But mass participation is best facilitated through organisations rather than in assemblies, especially assemblies with vague criteria for participating. The type of direct participation envisaged by the skeptics of parties and other mass organisations results in only the thinnest involvement in important decisions. The more people, the less that any one person’s input matters. In order to have substantial influence we have to organise in smaller sub-groups which leverage their collective labour. In addition, in order for the division of labour between these sub-groups to not be wasted there needs to be co-ordination between them and sovereign authority (both for society at large, but also for a particular organisation) that can make decisions when conflicts arise. Since it is important to keep the sovereign authority on a democratic leash, internal democracy — the freedom to organise, articulate criticism, change policy, replace leaders, etc. — is required. This applies to the shibboleth of the radical socialism, the recall of delegates. As we are not proposing an assembly system, we don’t wish the entirety of electorate to be able to exert a right of recall. Rather, control of the delegate should occur via the party: it should have the right of recall and if voters wish to exert that level of control, which would of course be welcome, they should join a party of a similar ideological disposition and be active within that.

There is nothing mystical about party forms of organisation which necessarily prevents the exercise of mass control over its representatives and leaderships. It mainly requires participation and the ability to dissent and there is no reason that mass organisations should be inferior to nebulous forms likes base assemblies in either of those. And the greater the degree of participation by the membership the more dependent the representatives will be on them, thus making it easier to exert control over them.

Not only is a mass party and the existing democratic system a superior strategy for dealing with the issue of the state, it also a more sustainable one democratically speaking because it is capable of lasting much longer than the initial period of revolutionary enthusiasm. The obverse of the mass participation of 1917 is the mass apathy of the 1920s, which led Trotsky to justify the dictatorship of the party.

We argued above that there is good reason to be cautious about changing extremely complex entities like a state bureaucracy. Nevertheless, it is worth considering improvements and the socialist organisations can be experimental grounds for figuring out what new procedural forms can actually function in mass institutions. So, something like sortition could be utilised for an internal party parliament which exercises oversight on the leadership between conferences.

Despite the shortcomings of parliamentary democracy, it remains the best gauge of public support for a political tendency. A socialist society depends on the support of the majority of the people, and that support needs to be publicly recognisable, i.e. it supporters and opponents alike agree that a socialist government has a mandate to implement its programme. The widespread acceptance of democracy as an organising principle gives socialism the chance of becoming the dominant political force in a country and of validating its actions in the transition. In fact, if the electoral system didn’t exist, it would be necessary to invent it.

The Coming Upheaval and Copernican Socialism

One of the elegant features of orthodox Marxism was its insight that the dynamic of capitalist expansion would lead to its eventual downfall. Capitalism, however, is still in expansionary mode, eating up the rural reserve of labour in Asia, pursuing the commodification of public services in Europe, and advancing technological development across the world. As long as it remains this dynamic it is going to be hard to surpass in productivity, especially given the level of co-operative production we are starting from. But if it is still expanding, it is also running into difficulties, as the problems in finding profitable investment opportunities over the last five years attests.

As capitalism develops and the means of production rise to ever more advanced levels, it must also must progress the automatization of the labour process, thereby squeezing the working class of its income and capitalist firms of their customers. Combined with the imminent ending of the rural reserve of labour and the increasing problems that workers, especially highly qualified ones, will have in finding opportunities for social advancement within the existing system, we can expect more and more working people to develop ideas of radical opposition.

Add in the pressure of climate change, increasing geo-political rivalry, and the severe rises in inequality it is conceivable that instability on a scale not seen since the early 20th century could return. At the very least, with transition to an information economy there will be opportunities for socialist production to demonstrate its superiority which is a precondition to winning mass support for socialism itself.

Although increased instability is likely, especially as the gross inequality of the current system leads to fragmentation within the elite itself, this does not in itself make socialism a likely outcome. This transformation to socialism can only come from the working class having a pre-existing organisational capacity to take advantage of these developments, especially in the most advanced countries, of which the United States is currently the most important. That capacity takes decades to build up and it’s not a process that can be rushed or circumvented by some clever shortcuts and nor should it be.

It is always tempting to think that we are special, that ours is a special nation or a special generation, one that could accomplish gigantic feats. But sober analysis tells us that we are more likely to be an ordinary generation located in a dynamic but ultimately fairly ordinary time.

That isn’t the end of the story however. Even if a successful insurrection is not on the horizon, it doesn’t mean that we have no role to play. Our short-term tasks do not involve overthrowing capitalism — a mode of production cannot even be overthrown — but to construct the organisations that someday will outcompete it, organisations which can survive even if the upheavals do not come soon, even if no opportunities for transition appear for years. Should we survive even that bleak a scenario with an eco-system of institutions intact, the next generation of socialists can start from a much more advanced point.

There is much in this world that is outside our influence, at least at this juncture, but institution-building is not. But it won’t be enough to try and persuade workers that a revolution or even socialism will solve their problems; rather we need to convince them that they have to do great things for the socialist organisation, that the future itself depends on us all playing our role in that great collective project, outside of which there is no salvation.

- Restricting the franchise to workers, as the Russians did, is completely unworkable for the principle organ of democracy in modern society. Likewise, the much vaunted unification of legislative and executive power is entirely counter-productive, draining the ability of the elected body to freely criticise the executive committees which must appear. ▲

James O’Brien is a member of the Workers’ Party Ard Comhairle.