Two years after the Bolsheviks took power in Russia, Petrograd, home of the revolution, was a devastated city. Severe food shortages had prompted the exodus of large parts of the population. A general opposing the new regime began an assault on the city, bringing his troops to the suburbs. But this did not stop a respected theater director from holding a lecture series on the history of art in an organisation called the Proletkult, even though the audience changed constantly because of military mobilisations. At the same time, the Proletkult theatre was preparing a performance written by a Red Army soldier for the second anniversary of the revolution.

Revolutions invariably challenge the cultural foundations of society, whether the participants consciously acknowledge this or not. Many Russian revolutionaries, like their Jacobin predecessors, welcomed the challenge. They were not willing to limit their goals to the establishment of a new political and social order. They hoped to create a new cultural order as well. But how would this be accomplished? All of the key concepts were open to dispute – the meaning of culture, the revolution’s power to change it, and the consequences that such change would have for the new social order taking shape.

In the early years of the revolution, the Proletkult (an acronym for proletarian cultural-educational organisations) stood at the center of these debates. It began just before the October Revolution of 1917, growing out of the work of factory committees, the most radical of workers’ organisations taking shape with the fall of the tsarist government. Although these new groups were originally focused mainly on economic issues, the inactivity of the Provisional Government, which had taken over after the ousting of Tsar Nicholas II, encouraged their expansion into the cultural field. At a meeting held just months before the October Revolution, factory committees proposed to create and new structure to unify and direct the proletariat’s cultural work.

Soon this new organisation took the name Proletkult. By 1918 it had expanded into a national movement with a much more ambitious purpose: to define a uniquely proletarian culture that would inform and inspire the new society. At its peak in 1920 the national leadership claimed some four hundred thousand members, organised in three hundred groups distributed all across Soviet territory.

The Proletkult’s vocal advocates believed that rapid and radical cultural transformation was crucial to the survival of the revolution. The leadership also insisted that the state support independent artistic, scientific, and social programs that would express the values and principles of the victorious working class. While skilled artists and intellectuals could help in the process, one of the organisation’s core values was autonomous creation. Workers should be the ones to create a new proletarian culture. Moreover, they believed there should be three independent paths to workers’ power: through unions in the economic sphere, the Communist Party in politics, and the Proletkult in the realm of culture. This insistence on independence proved to be one of the organisation’s most controversial tenets and soon put the organisation on a collision course with the Communist Party.

Although created by the revolution, the Proletkult drew on pre-existing programmes designed to educate and inspire the Russian working classes. The most radical was articulated by the Bolshevik intellectual Alexander Bogdanov, who had been an outspoken opponent of Lenin after the revolution of 1905. He believed that it was essential to educate a proletarian intelligentsia that would be prepared to take over a guiding role once the socialist revolution came. Bogdanov and his allies formed several small exile schools in Western Europe where they trained gifted workers in science and cultural history. Several of these students, like the worker activist Fedor Kalinin, became national Proletkult leaders after the revolution. However, the participation of leftist intellectuals like Bogdanov in this supposedly proletarian institution underscored one of organisation’s main dilemmas: how could one create a proletarian intelligentsia without the participation of those educated under the old regime?

Factory committees and unions formed another faction with a large stake in the new organisation. Legalised in the wake of the Revolution of 1905, these workers’ groups quickly became involved in cultural activities. They sponsored clubs, lecture series, art classes, and small theatres. They also opened up libraries stocked with the Russian classics and socialist literature. Newspapers and fliers came out of this milieu, where aspiring writers published their first poems filled with imagery about life in the factory. But even in this natural base for the Proletkult disagreements abounded. What kind of culture should the revolution sponsor? Would it be technical education so that workers gained the skills to run the factories? Should they focus on artistic work to inspire the new regime?

Participants in adult education classes and open universities also flocked to the Proletkult. Founded by charity groups and educational societies long before the October Revolution, these groups offered literacy courses and lectures in science and the arts for a broad audience. They were staffed by artists and intellectuals sympathetic to mass educational projects. For them, the Proletkult appeared to be a continuation of their original efforts. However, many of these well-intentioned teachers and artists faced suspicion from their students. Could the artistic and educational skills of non-workers help to build a proletarian culture?

The first Soviet Commissar of Enlightenment (or Minister of Culture) was Anatolii Lunacharskii, an ally of Bogdanov. He gave the Proletkult an independent budget to begin work. That money went first to the national organisation, which set up a rudimentary bureaucracy and started a journal called Proletarian Culture (Proletarskaia kul’tura). As the new government took over the possessions of the old ruling class, the Proletkult claimed part of the spoils. When the Soviet government moved to Moscow, the central Proletkult took over a large mansion once belonging to the merchant Savva Morozov on one of the city’s main boulevard. This process was repeated in the provinces, where local circles occupied public buildings and manor houses for their operations.

During the years of the Russian Civil War, from 1918-1920, the Proletkult expanded in a chaotic fashion across the country. Bolshevik power was tenuous, and the shape of the new state hardly fixed. This contributed to a kind of free-for-all, where local participants decided who would join and what their group would do. Requests for money, materials and most of all for leaders and staff members came from all kinds of cultural groups. The overwhelmed central organisation responded by sending out copies of Proletarian Culture and the minutes of the first national conference, documents that the locals were left to interpret by themselves. If they were lucky, local groups would also receive a small stipend.

Many provincial organisations did not honor the central group’s preference for seasoned industrial workers as members. The group in the river port and railroad town of Viatka (now Kirov), for example, welcomed all “labourers”, a word often used by the Bolsheviks’ opponents, the Socialist Revolutionaries, to apply to workers and peasants alike. A factory circle in Ekaterinburg opened its doors to everyone who wanted to improve their knowledge. The Tula organization even opened a short-lived children’s group, led by a teenager, whose stated aim was to free children from the petty-bourgeois family structure. In its early years, the Proletkult was more plebeian than proletarian.

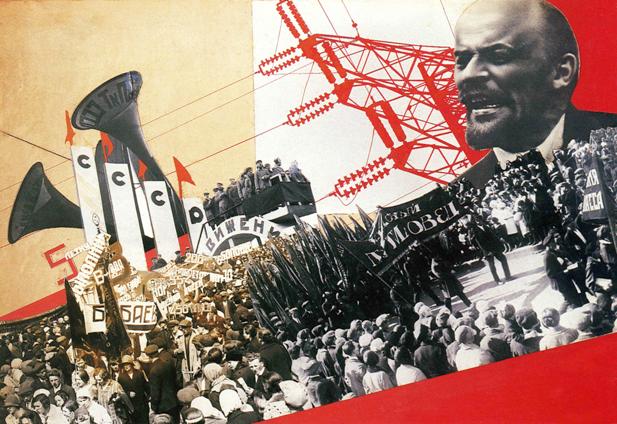

The organisation’s activities were as diverse as the membership. The products for which it was best known had a distinctly proletarian theme. Participants crafted poems, songs, plays, and paintings that lauded the factory as the inspiration for the new art. Well-known worker-writers like Mikhail Gerasimov published in the organisation’s many journals, and new authors sent in their work for consideration. Symbols of progress and beauty came from the industrial milieu, something apparent in the titles of many poems, like “Iron Flowers”, “The Iron Messiah”, “Machine Paradise”, and “We Grow From Iron”. In these creations, workers appeared as giants, titans, and masters capable of anything. Regardless of the social origins of the authors, sometimes submitted works about love and nature were rejected out of hand as unsuitable for a proletarian audience.

Agitational work was central to many local circles. Participants created posters in support of the Red Army and took part in ceremonies that marked new dates in the revolutionary calendar. Some organised mobile theaters and choirs to rally the troops on the fronts of the Civil War. In the summer of 1919, the Tula art workshop published a proud production report announcing that its members had made five hundred posters for the Communist Party, fifty-two for the teachers’ union, and three for local cooperatives. Here proletarian art had a decided political purpose: to ensure the victory of the new proletarian state.

Select Proletkult groups also participated in avant-garde artistic experiments. This trend was most noticeable in the visual arts, where important groups rejected “easel art” and “museum art” altogether and devised programs to unify cultural creation with factory production. Experimental theater, which turned against realistic methods, and experimental music, where artists devised new tonal systems, also gained small followings. Here the definition of proletarian culture was largely oppositional; these creations, in theory at least, marked a radical departure from pre-revolutionary artistic schools.

At the same time, many circles concentrated on bringing the teachings of Russia’s finest art schools to a lower class audience. Some of the best art teachers in Russia joined the new group, whether out of sincere ideological commitment or because they could get salaries and rations during the hard years of the Civil War. The big cities profited the most, but even the small town of Belev in Tula province had two instructors who had formerly taught violin and voice at the Petrograd conservatory. Public performances by groups like these were conceived as a way to train the tastes of the audience. Musical evenings included lectures on the life and times of the featured composer. The tried-and-true classics common in workers’ and people’s theaters before the revolution dominated local stages. The most popular plays were by favorite Russian authors like Alexander Ostrovsky, Nikolai Gogol, Anton Chekhov, and Maxim Gorky.

Rather than serving as a catalyst for a unified vision of cultural creation, the Proletkult served as a mirror reflecting the heterogeneous cultural world of the early Soviet years. The organisation combined folk music and Beethoven, mass recitations with standard lectures. Proletkult journals, some fifteen in all, showed this diversity of output. Here one could find strange juxtapositions, like poems about factories illustrated with cubist looking drawings and reports from the front next to a brief life story of Victor Hugo.

While the central Proletkult organisation demanded independence, its status within the emerging Soviet state was hardly fixed. Its activities often overlapped with many other groups. Its agitational work mirrored that of the Communist Party’s and its basic educational activities often duplicated that of the newly formed Commissariat of Enlightenment. There was no consistency at the local level. Some groups had excellent relationships with Party and government. Others did not. Local questionnaires sent back from the provinces to the center showed a wide array of institutional arrangements. In the early years of its expansion, an institution calling itself a Proletkult could have many functions: an entertainment center, a local school for adults, a village club offering literacy classes, or a tightly organised and exclusive factory cell. The flexibility of the Proletkult’s identity partially explains its popularity.

This period of exuberant expansion and eclecticism came to an end just as the worst of the Civil War wrapped up in the fall of 1920. With the Bolsheviks now firmly in charge, the central government began a sober evaluation of how best to spend its scarce funds. The Proletkult was particularly vulnerable. Associated with Bogdanov, an old opponent of Lenin, it appeared to have oppositional tendencies. Its initial demand for complete independence underscored that view. Lenin personally took on the organisation, denouncing its leadership and its goals. In a famous letter published in the Party newspaper, Pravda, in December 1920, he excoriated Proletkult leaders, its organisational practice, and its cultural mission. The Pravda letter was scathingly critical of the Proletkult’s demand for autonomy, which it portrayed as a petty-bourgeois attempt to establish an institutional base outside of Soviet power. It also attacked the programs within the organisation which tended towards “futurism”, a term used to condemn artistic experimentation. If workers wanted to improve their education, they should turn to the party and not the Proletkult.

This attack was part of a massive policy shift by the Communist Party as the Soviet state began to consolidate its power at the end of the Civil War. The working class was always a small minority in Russia, and the government now had to find a way to reach out to the peasant majority. The new state program begun in 1921, the New Economic Policy, was designed to do just that. Organisations like the Proletkult that aimed (at least in theory) to serve the proletariat alone were out of step with the changing direction. The government slashed the Proletkult’s budget and removed its autonomy, placing it firmly under the control of the Commissariat of Enlightenment. Any activities that could be accomplished through regular educational channels disappeared from the curriculum. Groups that operated in areas where there were few or no industrial workers closed. Very quickly the network of hundreds shrank to a handful.

It is important to note that the Party’s move against the Proletkult was part of a broader shift against institutions that claimed to represent the special interests of the working class. During the 1920s, unions lost much of their autonomy. Factions within the Communist Party that questioned the principles behind the New Economic Policy, such as the Workers’ Opposition, were put down with real force. And Lenin himself seemed to doubt the abilities of the class in whose name the Bolsheviks had taken power. Writing with Lenin’s encouragement and active participation, a chief ideologist for the Bolshevik Party, Iakov Iakovlev, wrote in Pravda in 1922 that the best elements of the working class had been destroyed during the Revolution and Civil War. The semi-literate elements that were left needed first to absorb the best features of the culture of the past before they could hope to achieve anything at all.

Discredited in both its political stance and cultural program, the Proletkult had to strike a new direction. It turned to activities in workers’ clubs, and focused especially on the theater as a way to instill pro-Soviet messages in actors and audience. Ironically some groups that survived tended towards avant-garde experimentation, despite Lenin’s denunciation of such trends. That was particularly the case in Moscow, where film director Sergei Eisenstein led theater workshops. The group there also took part in musical experiments, like concerts of factory whistles. Art circles gave up easel painting and began designing posters, book jackets, and union emblems. This kind of service work for union only expanded after 1925, when the organisation came under the control of the national trade union organisation.

In the meantime, many other new groups took shape claiming to represent the cultural interests of the proletariat. They existed in all media, but the most aggressive was the National Association for Proletarian Writers (VAPP). The members of this group attacked so-called “fellow travelers”, artists who supported the new regime but did not join the Communist Party. But they also attacked the Proletkult as a promoter of a false understanding of proletarian culture inspired by Lenin’s opponent, Bogdanov. In these continuing discussions about the evolving shape of Soviet culture, the Proletkult served primarily as a negative reference point.

Was the Proletkult ever a dissident movement, as it was portrayed by Lenin in 1920? That depends on how one defines the term. Certainly there were members who held very different views on the role of the Communist Party and the structure of the Soviet state. The vision of three paths to Soviet power, put forward at the beginning of the organisation, was always was a wild exaggeration of the Proletkult’s reach. During the Civil War such claims were quixotic. In the changed climate of the New Economic Policy, they sounded dangerous – even treasonous – to those who worried about the stability of the Soviet state.

In its reduced form, the Proletkult lasted until 1932. In that year the government disbanded all independent cultural organisations, particularly those that claimed to represent the proletariat. Instead, it planned large cultural unions and began to formulate an official Soviet aesthetic: “socialist realism.’ The new aesthetic was presented as the expression of a more advanced stage of historical development, a move toward a classless society. The state’s adoption of this new direction turned proletarian culture, supposedly the harbinger of the future, into the culture of the past.

In the early years of the revolution, there was a utopian element to all visions of the new society. Peasant dreamers prophesied a world without cities, and labor radicals foresaw factories without foremen. Leftist artists wanted to destroy museums and bring to the streets and the homes of the common man. Even Lenin, the most pragmatic of politicians, was briefly infected with this spirit; in his famous work State and Revolution, he depicted a governmental structure so simple and transparent that any cook could run the state. Proletkultists, as the self-proclaimed creators of the culture of the future, were inherently utopian. Their ideas and cultural creation were expansive and participatory, different from the emerging Soviet state program favoring basic education and labor discipline. This utopian vision did not survive the 1920s, but it was a crucial part of a revolution that sought to transform culture as well as political and economic life.

Lynn Mally is Professor of History at the University of California, Irvine. She is author of ‘Culture of the Future: The Proletkult Movement in Revolutionary Russia.’