To mark International Women’s Day 2021, the Workers’ Party held a memorial lecture in honour of Margaret O’Leary, long-standing Party member and former editor of the Party’s magazine, Women’s View, who sadly passed away late in 2020. Claire O’Connor, Workers’ Party Dublin Region organiser, examined the role played by working class and socialist women in the anti-fascist struggles of the last century, focusing on Dolores Ibarruri, Nora Harkin, and Sylvia Pankhurst.

It perhaps speaks to the way in which history can pigeonhole & compartmentalise the role of political women that Sylvia Pankhurst is mainly remembered today as the fighting, militant, Socialist suffragette. As a young woman, Sylvia found her voice in the fight for votes for women. However, this was only the beginning of an exceptional life on the Left.

She was born in 1882 in Radical Manchester to a family where fierce intolerance for social injustice ran strong in the blood: her descendants on both her paternal & maternal sides were chartists and protesters against the Corn Laws. Her father, Richard Pankhurst, with whom Sylvia was especially close in her early childhood, was a radical Republican barrister who ran unsuccessfully for parliament on a Socialist ticket.

Her mother was of course Emmeline Pankhurst, a towering figure in a generation that had been fighting for women’s suffrage, fighting across general human rights and feminist causes right back to Mill’s earlier petition 50 years before and the women’s property act – which Sylvia’s own father had been involved in drafting.

The second of the three Pankhurst sisters – the eldest being Christabel and the youngest Adela – Sylvia grew up against a background of activism in a deeply political family. The family later lived in London for a while to pursue Richard PH’s parliamentary prospects. They were always surrounded by an enormous diversity of political people – whether these were people working in the incipient Indian nationalist movement, abolitionists or indeed feminists.

This highly politicised childhood set Sylvia on a course which led her through tumultuous struggles, through prison gates, through the peak battles for women’s suffrage in the 1910s & through confrontations with political figures as diverse as Lenin, Shaw, Mussolini and even at one point a physical skirmish with Churchill.

She became a militant suffragette as a teenager, starting out as an activist in what was known as the family party – the Women’s Social and Political Union (WPSU) founded in 1906 & tightly controlled by her mother Emmeline. Its organising model was based on the union of garment workers in Manchester and Salford & the early women’s movement, which her sister Christabel was actively involved in.

Sylvia was first imprisoned at the age of 24 – and was one of the most arrested, most tortured and force-fed of all the suffragettes. During the period between February 1913 and July 1914 she was arrested eight times, each time being repeatedly force-fed. She provided graphic accounts in her writing of this ignominious chapter in Britain’s history of human rights abuses.

Indeed, many suffragettes later died as a result of the horrific traumas they suffered at the hands of the British Empire during this period. It is testament to the fierce resilience and fearlessness of this remarkably spirited personality, that Pankhurst went on to live such a full and long political life, despite the appalling & traumatising acts of violence she suffered as a young suffragette in her 20s.

Sylvia campaigned for the WPSU to take an explicitly socialist direction, tackling wider issues than women’s suffrage & linking it to a broader context of class struggle. She built a close relationship with British Labour Party founder Keir Hardie. Her socialist politics were made further evident in November 1913 when she spoke in support of Jim Larkin and the workers in the Dublin Lockout – an action which triggered her expulsion from the WPSU and represented the first in a series of grave disagreements with her sister Christabel and mother Emmeline.

This strained familial relationship famously broke down when Emmeline, and her sister Christabel became enthusiastic supporters of the campaign in favour of military conscription at the time of the First World War. Sylvia, by sharp contrast, was a pacifist. Later, in 1915, she gave her enthusiastic support to the International Women’s peace Congress held at The Hague.

The pacifist beliefs that she expressed during the Great War informed Sylvia’s views on the rise of fascism in the 1920s, even before Italy and Germany threatened the peace of Europe. With characteristic prescience, she was one of the first to recognise the danger posed by the rise of fascism in Italy – at a time when Churchill was expressing his admiration for Mussolini.

Throughout her life, Sylvia was a prolific newspaper editor and writer and it was in her ‘Workers Dreadnought’ magazine that her opposition to fascism first appeared. This was 1922, the year of Mussolini’s March on Rome, which marked the beginning of the rise of fascist governments in 20th century Europe.

From the beginning, Pankhurst’s opposition to fascism was expressed in explicitly socialist terms. She understood fascism as an agent of capitalism and the bourgeoisie, an interpretation of fascism (including German Nazism) that would be formally adopted by the Third International in 1924. While many British politicians demonstrated ambivalence in regard to fascism in the interwar period, Pankhurst’s views of it were consistently negative. She warned that far from offering anything new, this was a purely conservative movement, underpinned by a disingenuous exploitation of nationalistic and patriotic ideology, which ultimately sought to defend the established bourgeois order in a moment of capitalist crisis. Over time, her critique of fascism would become broader and more severe, when confronted with the rise of Hitler and the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War.

Sylvia’s anti-fascism was influenced by her partner, Silvio Corio, an Italian anarcho-syndicalist exile in Britain. From him and his metier of Italian exiles, communists and socialists – Sylvia learned early on of the rise on fascism in Italy. She travelled there with Corio and was involved in a skirmish with ‘squadistri’ or ‘Blackshirts’ in Bolgna.

She located this fascist organising firmly in the conditions of modern industrial society, describing Mussolini as:

“the renegade ex-Socialist who deserted the Party to join the jingoes in the war…..supplied with funds by the great industrial employers of Italy”

She consistently linked fascism to industrialism and more importantly to capitalism. “Let there be no mistake” she wrote in 1922, “Fascism is an international menace….the White Terror of modern capitalism….”

Sylvia urged her readers to recognise the dangers of nascent Italian fascism, warning that its rise spelled destruction for socialism and even the most minor victories won in term of workers’ rights. It stood for “aggressive and oppressive industrial capitalism” Sylvia also linked the rise of fascism to the failure of socialism, arguing in a 1923 editorial that:

“the Socialists, having failed to make good their promise to create a new society…..opened the way for Fascism to rebuild the old”

She continued to dedicate herself to exposing the truth behind male-dominated bellicose regimes and called attention to the harmful effects that war had on women by applying these same critiques to militaristic fascist regimes. In this way, her opposition to fascism was consistently influenced by her feminist standpoint and concern about the status of women.

She was critical of the British establishment’s apparent acceptance of fascism – particularly Prime Minister Bonar Law’s willingness to continue diplomatic relations with Italy after the fascist seizure of power – juxtapositioning this attitude with the response of the British government to the Russian Revolution. “The Russian Revolution was a menace to Capitalism,” Sylvia wrote, while Mussolini’s fascist revolution in Italy represented a “support to it and a ruthless attack upon the working class.”

Pankhurst highlighted the Mussolini regime’s targeted intimidation of communists and socialists, including those who still held political office. In an editorial she detailed how Italian Socialist MPs were subjected to physical abuse and police raids, despite the fact that they had been democratically elected. She also decried the practice of the government’s fascist squads in destroying the printing presses of their socialist opponents, while government officials were given final approval in the appointment of newspaper editors in order to censor all dissent.

She was active early on on the issue of Mussolini’s intentions for the ‘Empire of the Sun’ – his plans for revenge for Italy’s defeat in Abyssinia. Following the Italian invasion in 1935, she supported the armed resistance of Ethiopians against fascist occupation as “unwilling violence performed with amazing courage” and was a supporter of Haile Selassie. She linked the Italian-Ethiopian war to British colonialism, working to try to persuade the British state not to effectively form a protectorate and colonise Ethiopia by the backdoor. Furthermore, she warned that if Mussolini were let away with his racist, fascist war in Ethiopia, Hitler would be next.

After witnessing Hitler’s rise to power in Germany over ten years after the Fascist party took power in Italy, Pankhurst contended that “every impartial person who has studied Fascist and Nazi history and doctrine knows that its main feature is the violent elimination of opposition and the literal extermination of opponents who refuse to be silenced.” Violent suppression of opponents was therefore not unique to Germany or Italy but would occur wherever fascism took hold, according to Pankhurst, and therefore it could not be tolerated.

Sylvia conceived of women as ideal agents of anti-fascism, not least because fascism threatened women’s rights and the legacy of the suffrage movement. As was the case during the First World War, she viewed women’s absence from international politics as one of the reasons that international peace had been violated and would continue to be threatened. She wrote:

“In view of this danger, I utter the strongest appeal I can to women: ROUSE YOURSELVES AGAINST FASCISM…it certainly means war”

She believed that women were better suited to be pacifist activists than men because “the most untutored woman knows in the depths of her heart that war is war, whether the people who are massacred live in Europe or Africa” and called on international women’s organizations to take action to mobilize international opinion against the atrocities perpetrated against women in Ethiopia.

In doing so, Sylvia continued to carve out a space in the anti-imperialist and anti-fascist movement for women activists, whom she viewed as natural advocates for peace and as such essential actors in the fight to secure lasting peace through international cooperation and involvement in the political system.

While Sylvia Pankhurst was supporting the fight against fascism in Italy and Ethiopia in 1936, another revolutionary woman was solidifying her role in history as an iconic and implacable opponent of fascism. Dolores Ibarruri was emerging as a legendary figure of the Spanish Civil War.

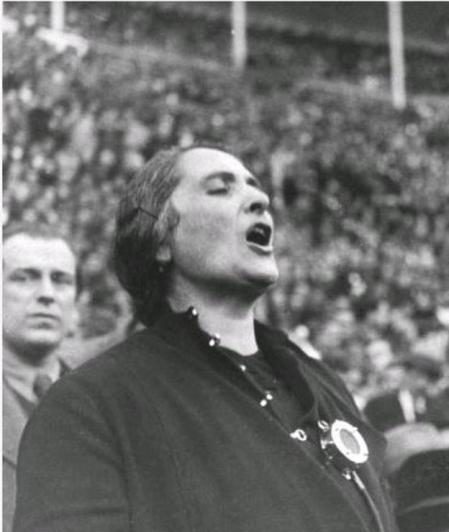

‘La Pasionaria’ – or the ‘Passionflower’ as she was known – was a fiery orator, inspiring many thousands of workers through her speeches in the streets of Madrid on behalf of the PCE – the Spanish Communist Party. Her famous ‘NO PASARAN!’ speech marked the beginning of the Spanish Civil War, a nearly three-year struggle between the sitting democracy and Franco’s fascist coup.

“Workers! Farmers! Anti-fascists! Spanish Patriots!,” Ibarruri cried to the crowds in Madrid in July of 1936. “The whole country cringes in indignation at these heartless barbarians that would hurl our democratic Spain back down into an abyss of terror and death.”

This was a call to unify, a plea to Spain to defend itself against the combined forces of Franco, Nazi Germany and fascist Italy as they approached the Spanish capital. Her words would become the most recognizable anti-fascist battlecry of the era. No pasaran – they shall not pass!

Born in 1895 to a Basque miner and a Castillian mother, Ibarruri grew up in Gallarta, but later moved to Biscay and joined the PCE when it was founded in 1921. She was the eighth of 11 children, quitting school at the age of 15 to work as a seamstress and later a cook. As a child she had aspirations to work as a teacher but poverty prevented her from completing formal education. This working-class childhood fuelled in the young Dolores a hunger for social justice and strongly informed her later interest in Socialism, which she explored with her husband, miner and trade union organiser, Julián Ruiz.

In 1931, with the advent of the Second Spanish Republic, Ibarruri moved to Madrid. Soon she was writing political articles for the PCE publications under the pseudonym ‘passionflower’ and delivering passionate speeches, always clad in black. In a letter, published in Pravda, to the Soviet actress who had played her in the 1936 play Salut, Ispanii!, Ibárruri attributed her success as an orator to her ability to express — to become — the suffering and courage of the Spanish people: “My voice is the outraged cry of a people that does not wish to be enslaved . . .”, she wrote. “In my voice sounds the cry of mothers, the lament of women in bondage, demeaned and scorned.”

Ibarruri put this flare for drama and impassioned oratory to good use, travelling around the country to negotiate the release of political prisoners and lift the spirits of revolutionary militias fighting on the front line against Franco’s dictatorship. She encouraged people to fight with knives and hot oil in the face of lack of weapons and made such famous exhortations as:

“It is better to die on your feet than to live on your knees”

La Pasionaria advocated to improve working, housing and health conditions as well as land reform and union rights. The fascists were terrified of her and spread propaganda that she was secretly a man who had killed priests with her bare hands. In 1933, she founded the Association of Antifascist Women (“AMA”), a women’s organization which carried out a crucial role fighting against the rise of Franco’s army.

As the civil war developed Ibárruri become a key figure. She was one of the most senior figures in the Popular Government and the Communist Party of Spain – at a time when few women rose to that level of prominence. “The name of La Pasionaria sums up an entire era in the struggle of workers and the Spanish people for freedom, democracy, and progress,” Cuban President Fidel Castro later wrote in an article published for Ibárruri’s 90th birthday.

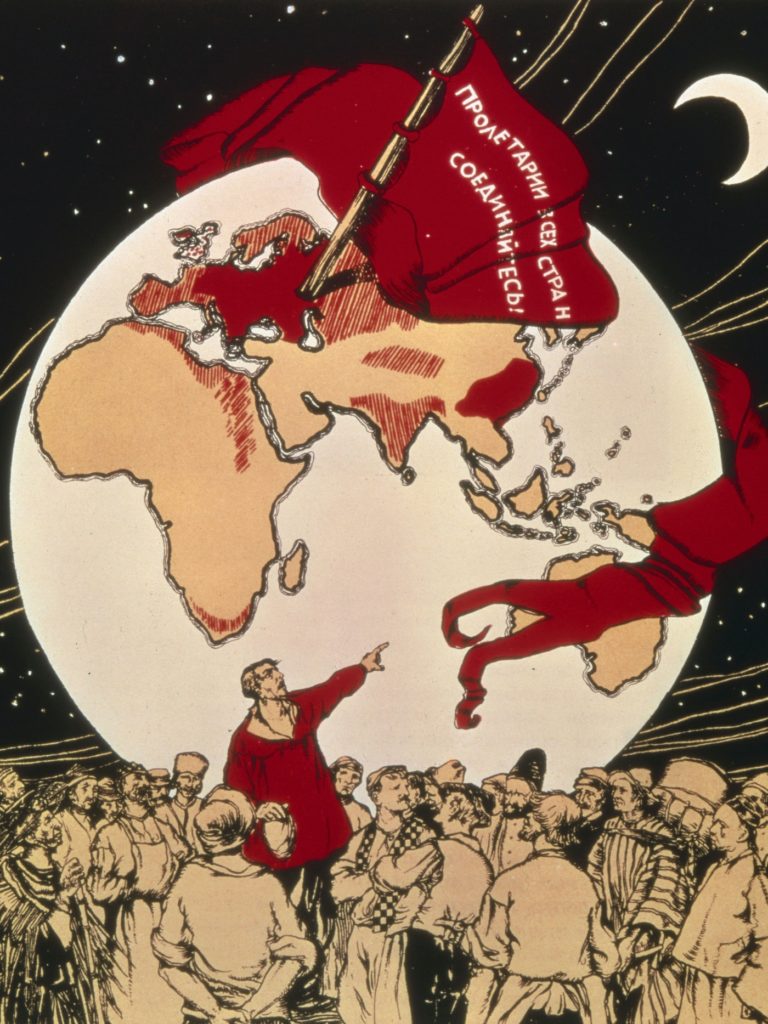

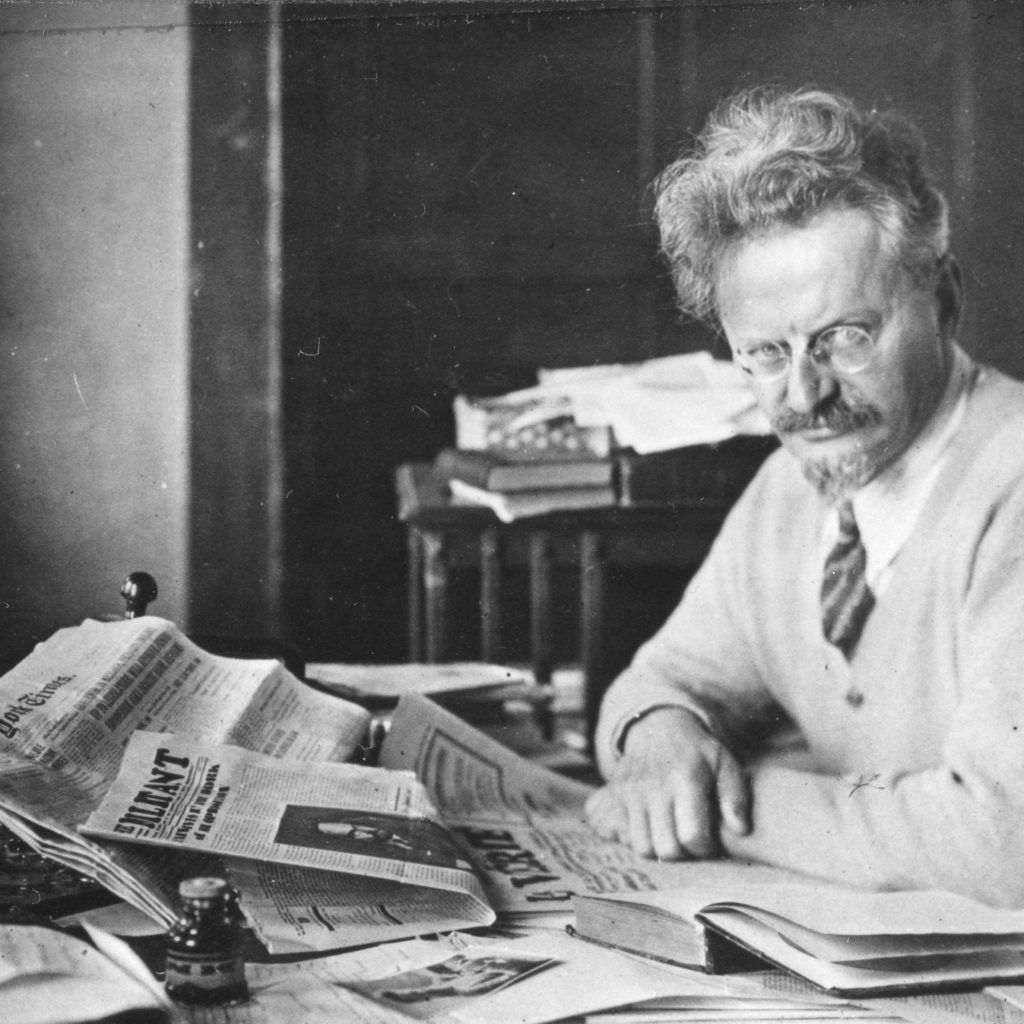

The forces aligning in Spain would soon be reflected in the Second World War writ large. While Franco’s nationalist forces received support and ammunition from Nazi Germany and fascist Italy, the revolutionaries were aided by the USSR and socialist Mexico — with the international brigades volunteering to fight on their side as well. Ibárruri led efforts to unify the left under a single army. As the civil war developed, and Trotskyists fought with the communist elements and the republican movement began to become splintered, leading Ibárruri to refer to the Trotskyists and Anarchists as the “Fascist enemy within”.

After Franco won the war with Italian and German assistance, Ibárruri was exiled from Spain. She relocated to the Soviet Union in 1939, where she was reunited with her family and was part of a small but powerful contingent of exiled Spaniards in the USSR. Tragically she also lost her son Rubén to the struggle against fascism: he made the ultimate sacrifice fighting heroically against Nazi fascism in the battle of Stalingrad.

Whilst in the Soviet Union, Ibárruri maintained her support for her comrades in the PCE and across Europe and worked as part of the Executive Committee of the Communist International Secretariat at the Communist International. She continued to write at length in support of those fighting against fascism across Europe, linking this to her support for Stalin and the Soviet Union. She was appointed General Secretary of the Communist Party of Spain, a position she held from 1942 to 1960, before then being named honorary president of the PCE, a post she held for the rest of her life.

The Civil War heroine outlived Franco and returned from exile to Spain on May 13, 1977, some 18 months after Franco’s death and 34 days after the Spanish government again legalized the Communist Party.

Upon her return she was duly re-elected – at 82 years old – as a deputy to the Cortes in the country’s first democratic elections since Franco’s death, again for the region of Asturias- the same region she had represented under the Second Republic.

Any discussion of the Spanish Civil War on the Irish Left must of course include the roughly two hundred Irish people who went to Spain to fight against Franco and fascism in the international brigades – military units set up by the Communist International to assist the Popular Front government. Our volunteers fought at Jarama, at Madrid and at the Ebro among other places – and over 60 never returned home.

Nora Harkin was a founder member of the Spanish Aid Committee, a group that organised support in Ireland for those that went to Spain to fight fascism.

Harkin was born in 1910 in Donegal to an anti-Treaty Republican family and was first politicised as a teenager, helping to address campaign envelopes for the republican candidate in a 1924 byelection. She left Donegal at the age of 21 to work in the Irish Hospital Sweepstakes in Dublin where she met her husband, Clan na Gael activist, and later a founding member of the Republican Congress, Charlie Harkin. She also worked closely with Dublin Republican Socialists including Peadar O’Donnell, George Gilmore, and Frank Ryan.

Harkin became a member of the Republican Congress executive – regularly participating in street protests and demonstrations which were cleared by baton charges by the Gardaí. Her politics were firmly Socialist Republican, rejecting the brand of militaristic and chauvinistic nationalism espoused by Eamon Dev Valera. Harkin was also strongly opposed to the subjugation of women in the 1937 Constitution.

She worked on the Spanish Aid Committee alongside leading members of the republican, socialist and Communist movements in Ireland at the time, including Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington as Chairwoman, John Swift, Nora Connolly-O’Brien, Dorothy Macardle, Ernie O’Malley and Fr Michael O’ Flanagan.

The committee was set up against the backdrop of a conservative, Catholic Ireland where the overriding consideration of the Catholic population was for the plight of the Spanish Church. The Catholic Church in Spain had lent its support to Franco’s Nationalists on account of owning considerable land – unlike its Irish counterpart – and was threatened by the redistributive policies of the Popular Front Government.

Inevitably there was violence and deep hostility between the Spanish church and the organised workers who had formed militia units across the country to defend themselves against the Franco-led insurgents. This led to clerical condemnation of hysterical proportions from the pulpits of Irish parish priests across the Free State, who decried the reported atrocities committed by ‘Reds’ against the Spanish church. While the Fianna Fáil government remained neutral, the opposition and virtually the entire press were vociferously pro-Franco.

Against this incredibly hostile background of ostracization and reaction – including recurring episodes of violence and confrontations on the streets of Dublin between members of the Republican Congress and O’Duffy’s Blueshirts – the Irish radical Left remained determined to offer some kind of cohesive support for the government in Spain. O’Duffy started the Christian Front in opposition to the Left’s support for the International Brigades.

Speaking of this period in an interview in 1996, Harkin commented:

“It was the people, the ordinary down to earth people like ourselves from our country…..who were anti-Franco. Those were the people we supported because we felt that’s who we would have supported in our country had the positions been reversed. We had a committee going, we collected a bit of money to be able to pay the lads something when they came back. And we were able to give them a few shillings a week for a couple of months…..We went round and we begged, we went round our friends and we badgered them into giving us a half-crown a week, so we had support in that way. But it was very mild, very low-key….”

Harkin also spoke of witnessing young men leave, some never to return, and how one of the largest church-gate collections in Ireland since the time of the Daniel O’Connell, was held in aid of Franco.

She drew a parallel between the struggle of the Fenians in the 19th century and that against fascism in the 20th century. I quote:

“There’s always a freedom to fight for – it comes in different guises, if there’s an oppression or something, that young people feel is wrong, they’ve got to try and put it right…..”

Harkin went on to help form the Ireland-USSR Society with Frank and Bobby Edwards and trade unionist John Swift among others. She was also a founding member of the Irish Anti-Apartheid Movement and organised the sending of material support to prisoners and their families alongside Kader Asmal throughout the 1970s. Furthermore, her political activism extended to considerable voluntary work for the Irish Family Planning Association throughout the 1970s and 80s. Befittingly, this unshakably energetic Socialist lived to the remarkable age of 101.

CONCLUSION

It is important to note that – interesting as this talk may be – we are not remembering these heroines of the anti-fascist movement for reasons of nostalgia, nor as just an interesting academic exercise on International Women’s Day.

On the contrary, as members of the Workers’ Party and as Socialists, we return to Pankhurst, Ibarruri & Harkin seeking guidance in our approach, in a current international context where the spectre of neo -fascism and far-right extremism once again haunts the landscape.

These three remarkable revolutionary women understood the importance of a feminist politics which is concerned with more than just equality of women to men.

They understood the essential class character of the brutal assault on humanity which the rise of fascism represented. The reality is that the phenomenon of fascist organising always remains centred on perverse eccentricities on the periphery of politics – until it is embraced as a last resort, armed and equipped to threaten humanity, by desperate elements of the bourgeoise in the context of the collapse of the Capitalist economic order. Thus, we revisit these women on this symbolic day to re-assimilate the lessons of their analysis and draw inspiration from their heroinism.

More than simply recognising the class character of capitalist society and the fascist menace that it throws up, however, all three women understood the central importance of working class political organisation to defeating it. They did not remain detached from the working class as independent voices but sought to build, and played a central role in building, mass organisations that could campaign and fight for working class interests and for socialism.

Finally, they also grasped the international character of the battle they faced. They understood our common class interest across nations in defeating capitalism and the importance of practical political solidarity in the face of their common enemy. In an increasingly globalised world, we, as socialists, should reflect on the important role that building strong international political and organisational links will play in winning the battles we will face.

I’ll conclude with a quote from the great revolutionary Clara Zetkin, the founder of International Women’s Day, who although mortally ill, travelled from Moscow to confront the Nazis, presiding at the opening of the newly elected Reichstag in August 1932;

“When the men are silent, it is our duty to raise our voice on behalf of our ideals.

When the men kill it is up to us women to fight for the preservation of life”.

Claire O’Connor is a member of the Workers’ Party in Dublin.