The French Communist Party (PCF) and the Italian Communist Party (PCI) emerged as two of the largest communist parties in Western Europe in the aftermath of World War 2. Éilis Ryan gives an overview of their histories in the post-war period.

Introduction

In the late 1940s and 1950s, France and Italy were home to the two largest communist parties in the developed capitalist world. The two countries were regarded as the only two western democracies where communists, and not social democrats, dominated the political left after the second world war.

As well as their size in the late 1940s, the two parties share a common origin to their growth. During World War 2, the resistance movement in each country was world-renowned, led and dominated by communists, and hugely popular domestically. And in both cases, the communists emerged from the war at a size which made them real competitors to becoming the largest party in their respective parliaments.

So, what happened? Why did that success and growth not translate into long lasting power? This is the question this article seeks to address.

Throughout this article, the terms used to describe various ideologies and parties are those commonly used in Ireland. The term ‘Social democrats’ is used to describe parties with the style of politics generally in line with social democratic and labour parties in Ireland, although in France, for example, the party ascribing to that politics is called the socialist party (PS). In Italy, the Christian Democrats could also be termed quasi-social democratic during the period in question.

Mass Communist Parties in Western Europe after the First World War

The Second International grouping of socialist and labour parties, which had been brought together internationally from 1889, began to fall apart from 1915 onwards, and its last formal meeting took place in Geneva in July 1920. This was largely due to differing attitudes towards World War I, with views ranging from full support for war credits to finance the war, to neutral stances to full opposition. In addition, differences in relation to the 1917 October Revolution came to the fore in the same period.

These differences played out within most members of the Second International, including the French section of the Workers’ International (SFIO) and the Italian Socialist Party. In France, the French section of the Workers’ International (SFIO) held a congress in 1920, in which a majority of members voted to join the Comintern. They went on to form the French Communist Party (PCF). Significantly, the PCF was the only Second International party in Europe in which a majority of members chose the communist path at this juncture. In Italy, the Italian Communist Party (PCI) was formed as a split from the Italian Socialist Party in 1921.

The newly-founded PCI and PCF became members of the Communist International (Comintern) which was formed in 1920. The hope of the post-1917 period, and the focus of the Comintern on a very real possibility of world revolution, gave way to the swift suppression of communist parties in many western European countries, and both the PCI and PCF were banned during the period. With the rise of fascism, the Communist International adopted a ‘popular front’ strategy of cooperation against fascism in 1935 at its Seventh Congress. By this point, the PCI had been banned for nine years, and the PCF received the same treatment in 1938. This was ostensibly because of its membership of the Comintern, and later justified by the Soviet Union’s decision to sign a non-aggression pact with Nazi Germany.

1943 saw the end of the Comintern in favour of a nominally looser configuration with individual countries’ circumstances playing a greater role in setting the direction and agenda of the Communist Parties’ strategy and tactics.

Resistance

Between 1935 and 1945, the membership of communist parties outside the Soviet Union grew from 1 million to 14 million. In Italy the party grew from 5,000 members in 1943 to 2,000,000 in 1945. In France the party grew from 300,000 in 1939 to 1,000,000 in 1945. The single biggest reason for this growth was both parties’ strength within the partisan movement which fought fascism.

The PCF comes in for some criticism for not beginning an active, armed resistance until after 1941, something interpreted as evidence of deference to Stalin and in his non-aggression pact. This is somewhat misleading; active appeasement was the policy of the capitalist parties until 1938, and no other left group took up armed resistance prior to 1941 either. The PCF’s primary publication, L’Humanité, maintained a staunch record of opposition to anti-Semitism under the Vichy regime, as early as October 1940.

From mid-1943, the PCF played a leading role in the French Conseil National de la Résistance (CNR), the French National Council of the Resistance which co-ordinated the partisan movement. The liberation of Corsica in particular consolidated its popular reputation. By 1944/45 it was known as “the party of 25,000 executed activists” for the high toll its militants had payed in the resistance. Its popularity and effectiveness forced capitalist opponents of fascism to accept the PCF’s presence as a major player.

In Italy, the resistance really only began in 1943 after the flight of the King. The resistance coincided with United States occupation of Italy from 1943-45. Palmior Togliatti, exiled leader of the PCI, returned from the USSR in March 1944, and in April 1945 Milan and Genoa, two of the Italy’s primary centres of wealth and industry, were taken by the communist-dominated partisans. In all, 30,000 Italian partisans were killed, and again the communists far outnumbered the Italian Socialist Party (PSI).

France and the PCF after World War Two

On 21st October 1945, France voted to elect deputies of the first post-war government, with a restricted mandate authorising them to author a new constitution for the Fourth Republic. The three parties which had made up the Resistance, together with Charles deGaulle, ran on a common programme of a welfare state and the nationalisation of banks and industry, broadly in line with the programme of the Resistance.

Together, the socialists and communists won just under 50% of the vote, and drafted a constitution which would see France transform to a unicameral system, scrapping the Senate and resisting De Gaulle’s proposed presidential system. De Gaulle resigned in January 1946 in protest. A referendum on the new constitution took place in May 1946. The referendum fell, amidst accusations that the proposed constitution would herald in Marxism and the abolition of private property. A new assembly, tasked with drafting another constitution, was elected the following month, and the Christian Democrats gained pole position. Its constitution passed narrowly (acquiring a lower popular vote, in fact, that the Communists’ draft), and the fourth republic came into existence.

In November 1946, the first full elections of the French Fourth Republic took place. The PCF won 28% of the vote and some 182 seats. With 5.5 million votes, they had become the largest party in the state. The PCF’s leader, Maurice Thorez, claimed a mandate to lead a left government, but the smaller two parties of the broad left electoral alliance refused. Instead, the PCF joined the cabinet of a government led by social democrats, but they were swiftly dismissed in 1947. The dismissal saw the beginning of the “Third Force” coalition against communism, which united social democrats, centrists and liberals until 1958.

For the next decade, over a quarter of the electorate continue to vote communist. However, a constitutional amendment introducing two-stage voting meant that, in spite of the PCF’s vote share holding steady at 20-25%, in 1958 their share of seats in parliament reduced from 25% in 1956 to just 2% in 1958.

The same 1958 referendum strengthened the Presidency and watered down the powers of the National Assembly, and from 1958 – 1981, the right held both the Assembly and the Presidency.

PCF 1945-1958: Enforced exile or ‘stalinist’ isolationism?

The communists’ influence in these initial years after the war was enormous. To give a sense of it, in 1947, a strike began at a major Renault factory (newly nationalised). Of the 30,000 workers present, 17,000 were communist party members. Despite not leading the government, they held the clear upper hand.

In their brief period in government, the party held five ministerial posts. The government undertook a widespread programme of nationalisations, including of the coal industry, the Parisian transport system, five major banks including the Banque du France and Credit Lyonnaise, 34 major insurance companies, and a host of companies accused of wartime collaboration, such as Renault. Work councils were established in all workplaces of 50 or more people. The distinction between men and women for the purposes of setting wages was outlawed, and workers were given legal positions in how state pension and social security funds were used.

There are some attempts to paint the Party’s electoral strategy as driven by their orientation towards Stalin and the Soviet Union, with the PCF’s turn towards left electoral alliances from the late 1950s put forwards as evidence of ‘de-Stalinisation.’ Far more likely, this turn towards alliance came as a response to the significant amendment in the electoral system brought in with De Gaulle’s fifth republic, which saw the PCF’s seat share drop so dramatically.

Meanwhile, between 1947 and 1978, the PCF won either the largest or second largest share of the popular vote in every single election which took place. Such results cannot be sustained through ‘isolationism,’ regardless of whether or not a party joins government.

The PCF’s successes right up until the late 1970s were sustained by its deep and consistent engagement in trade unions, community organisations and workplaces – the antithesis of isolationism. The exclusion of a party of such strength from government should be read not as evidence of the PCF’s puritanism, but of its opponents’ understanding – both in France and in the United States – that, if allowed to govern, it would have been unstoppable.

The PCI in Italy after 1945

“Always remember that the aim of the insurrection is not the imposition of political and social transformations in the socialist or communist sense. Its aim is national liberation and the destruction of fascism. All other problems will be solved by the people through free popular consultation and the election of a Constituent Assembly once the whole of Italy is liberated.”

Instructions to All Comrades and to All Party Cadres

Togliatti, 6 June 1944

The Italian Communist Party won 20% of the popular vote in the first post-war elections, and was in government from 1944 to 1947.

In May 1947, Italian Prime Minister De Gasperi dissolved the government, ostensibly owing to a political crisis involving the murder of 11 peasants in Sicily. However, De Gasperi has since made clear that his decision to dissolve the government was driven primarily by the United States. Both Us Secretary of State George Marshall and US Ambassador to Italy James C Dunn made clear to De Gasperi that Marshall Aid was dependent upon him dissolving the coalition and removing the communists from government.

Fresh elections took place in 1948, dominated by the interventions of the United States. Historian Paul Ginsberg described the United States’ role in the elections as “breath-taking in its size, its ingenuity and its flagrant contempt for any principle of non-interference in the internal affairs of another country.” US$176 million of aid was granted to Italy in the first three months of 1948, before the elections. Each shipload of medicine and food would be met in Naples or Genoa by US Ambassador Dunn, where he would give a speech to waiting media endorsing the Christian Democrats. On 20th March 1948, US Secretary of State Marshall warned the aid would cease in the event of a Communist victory.

Italian-American Hollywood stars were enlisted to record messages of support for the Christian Democrats. American Cardinal Francis Spellman, in the presence of President Truman, used St. Patrick’s Day to tell media, “One month from tomorrow Italy must make her choice of government, and I cannot believe that the Italian people will choose Stalinism against God, Soviet Russia against America.” Military plans for intervention were in place in the case of a Communist victory, and US warships anchored in the Italian ports leading up to the elections.

The Christian Democrats won 48.5% of the vote. In the face of such opposition, the PCI still increased its deputies from 106 to 140 between 1946 and 1948.

Togliatti is shot

On 14th July 1948, Palmiro Togliatti was shot. With US warships still in Italian ports, and in the aftermath of the election, the attack was immediately interpreted as the beginning of an onslaught on the left. Militants responded with a fairly spontaneous uprising, strongest in the industrial cities of the north.

Workers occupied the Fiat factories in Turin, taking 15 hostages. In Genoa, communist activists took clear power. A trade union member of the PCI said in Genoa on 14th July 1948;

“That evening, Genoa was in the hands of the people, so much so that the police rang the ex-partisans’ association saying ‘Send me a group of partisans to defend the police headquarters, because I’m completely isolated here.’”

The leadership of the Communist Party intervened to bring the insurrection to an end. De Gasperi responded with total repression, in one town putting 147 inhabitants on trial. From 1948 until the 1980s, the PCI received between 25% and 35% of the vote in every single election. By the mid-1960s, the US State Department estimated the Italian communists had approximately 1.5 million members. Its electoral popularity peaked with 12 million votes in the mid 1970s.

Beyond Elections: Life in the PCI and PCF Post-WW2

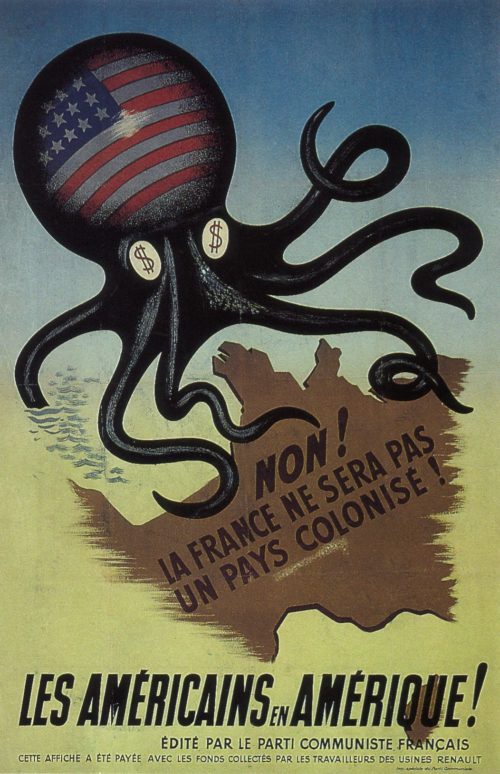

The PCI and PCF were kept out of government by an unprecedented stream of anti-communist propaganda, foreign military threats, and bribery of the French and Italian governments in the form of aid and loan conditionality, all of it driven by the United States. But none of this was sufficient to reduce the popular depth and strength of support for the two parties, well beyond electoral successes.

Peasant Support

In both Italy and France, one of the major changes in the composition of the two parties in the post-war era was the growth in support amongst peasants and the rural poor, where conditions had barely moved past feudalism in many instances. Tuscany for example, one of the heartlands of the resistance and a growing PCI stronghold, was still on the whole farmed through Mezzadria, or sharecropping. Some 90% of land in Siena province was farmed under a sharecropping system in the 1950s. In the post-war period, a demand for tenure security and the right to unionisation and welfare entitlements (i.e. normalisation as workers), politicised this area further. The PCI attempted to organise these in a somewhat modern way, with some limited success. The party organising co-ordinated withholding of crops in 1945, and helping to organise a campaign for housing rights largely focussed on removing animals from the home.

The success of the PCI in politicising – not simply organising – the peasants is particularly clear in the anti-war campaigning of Tuscan peasants in the 1950s. In 1951, Tuscan sharecroppers organised an anti-war protest in Siena against the visit of Dwight Eisenhower. In 1952, the ‘peace partisans’ of Montalcino collected 8,000 signatures from their peasant commune calling for a ban on nuclear weapons, after the 1952 nuclear tests in the island of Bikini. In 1951, peace flags were flown from haystacks and trees across Siena and Umbria, in opposition to the establishment of a NATO base on the Tuscan coast. Much of the peasant propaganda about the campaigns draws comparisons between the new US occupation and the German occupation.

Patriotic emphasis

After World War Two, both PCI and PCF developed a national tinge to their politics. In large part this resulted from their association with the partisan movement. It was also tactically chosen by the leadership to counteract propaganda aimed at tarring communists as Russian agents. The PCI’s new constitution, adopted after WW2, required the Italian national anthem be sung after party meetings along with the Internationale and Bandiera Rossa.

Alongside this, and in particular in Italy, came significant compromise with social conservatism in many ways – emphasising the importance of the family unit, and adopting somewhat traditional views on women’s roles. Undoubtedly, the PCI remained far more progressive than its rivals, nonetheless.

The communist party form

The parties were often typecast as the traditional, Leninist PCF compared with the PCI’s ‘partito nuovo’ or new party – what Togliatti deemed “An organisation which is in the midst of the people and satisfied all of their needs as they appear to the mass of the people.”

A revolution abandoned or realpolitik?

The French and Italian communist parties soared to success in the mid-1940s, without ever consolidating this into either decisive electoral victory or revolution. The two parties could boast enormous electoral gains, growth in trade unions, millions of members, even more millions of voters, and a decisive impact on forcing the social democratic forces in both countries well to the left. Nonetheless, all the time these gains remained embedded in the liberal democratic order.

So was it a wasted opportunity? Did the two parties in Italy and France refuse to “complete” a people’s revolution, and capitulate to the liberal democratic parties, because they were following Stalin’s orders?

Certainly, in Italy and France, in 1944-45, the strength of the communist organisations, the defeat of fascism, and the militant nature of the trade union movement (generally associated with the communists), meant that in both countries it appeared there was a very real possibility of the complete overthrow of capitalist government in those countries, and the establishment of communist governments. And no doubt, the PCF and PCI were heavily influenced by Soviet decision-making in the period.

And certainly, also, the relative post-war stability in France in Italy can make it appear that there was little risk involved in pushing further, beyond Togliatti’s liberal victory over fascism and for revolution.

That line of thinking is of course far too simplistic. Examining the Greek case, for example, the strategy of ‘forging ahead’ with communist revolution had arguably worse results than that in France and Italy. When it looked as if the communists were winning in Greece, the UK and US stepped in to defeat them. Then, in 1949, after their defeat, the communist party were once again outlawed. The future leaders of the Greek junta began to immediately receive $1million a year CIA funding. A weak liberal democracy lasted barely more than a decade before a military junta came into force.

Truman, Marshall and Gladio

The simplistic line of thinking also ignores the reality of what the US actually did to deter and defeat the communists in 1945 – 1947.

The Truman Doctrine came into force in April 1947-48 declaring that the containment of the Soviet Union was a primary objective of US foreign policy. This was used in the immediate term to justify the invasion of Turkey and Greece to ensure communists there did not gain from their role in the defeat of fascism.

It was soon followed by the Marshall Plan. There has been some debate as to whether communists were forced to refuse Marshall aid by the Cominform, or whether the US made their exclusion from government a condition for disbursing that aid. Given events in Italy in 1948 described above, it seems fairly clear the latter was the case. In total, Italy received $1.2 billion in funding, and France received $2.2 billion under the Marshall plan – once the communists had left government. Announcing the fund, George Marshall said “Its purpose should be the revival of a working economy in the world so as to permit the emergence of political and social conditions “in which free institutions can exist,”(emphasis added).

5% of funds disbursed under the Marshall Plan went directly to the CIA to fund its covert and open operations in the recipient countries. This money was used to establish labour unions and cultural fronts to rival communist-dominated organisations. These CIA- funded institutions were generally dominated by ‘leftist’ anti-communists, rather than the right.

Perhaps the least well-known and most insidious factor limiting the democratic expansion of communists after World War Two was Operation Gladio. NATO’s predecessor organisation took a decision at the end of World War Two to establish covert ‘stay-behind’ cells in western European countries, which could be activated in the case of a communist uprising. It was directed and funded by the CIA, and in many instances involved the recruitment and training of fascist / ex-fascist militants to lead the covert cells. The Washington Post reported that the CIA referred to one German cell member as an “unreconstructed Nazi.” In the early 1990s, the Italian government uncovered 167 weapons dumps which had been under the control of these covert cells.

The Balance of Forces in 1940s Italy and France

Finally, an examination of the balance of military forces in 1945 makes clear that, had for example Togliatti pushed ahead for a communist revolution in 1948, the Italian communists would have been slaughtered. Already weak, 30,000 Italian communists had been killed by 1945. By contrast, the United States had war boats stationed in most major Italian ports and was already negotiating permanent military bases.

Were the Italian communists ‘abandoned’ by Stalin and the USSR? In 1945, the Soviet Union had lost 15% of its population – some 20 million casualties to the war. Soviet GDP fell by 34% between 1940 and 1942 and did not recover until the mid-1950s. By contrast, the US unemployment fell from 25% to 10% during the war and its economic was so dominant that its dollar became world’s reserve currency in the war’s aftermath. Its national infrastructure was completely untouched, even boosted by the war.

The ‘counter-history’ supposes that, had the European PC’s pursued full revolution, instead of capitulating to opportunism and Stalin’s diktat, they could have established full people’s democracies post-1945.

The reality is that to attempt to do this, judging the US by its later actions, would have required direct and immediate armed confrontation between the Soviet Union and the United States, and would have meant plunging the USSR from a conflict which cost them 15% of their population, into another against a country dramatically strengthened, economically and ideologically, by World War Two. Domestically in Italy and France, the well-armed partisans would have faced the hundreds of thousands of US troops still stationed in those countries.

Were the PCF and the PCI prioritising their alliance with the USSR in their decisions to hold back from revolution? The flaw in conceptualising the question in that way is to assume that prioritising alliance is always a matter of subservience, rather than tactics. What hope would revolutions in France and Italy have without alliance with the USSR, in the face of US anti-communism?

Togliatti gave his view in 1960 on the possibility of full communist revolution beginning in Genoa in 1948, saying: “Certainly, an insurrectionary attack – and its inevitable defeat – either in 1946 or 1948 would have suited some comrades well. No danger of the bureaucratization of the party in that case! And the so-called ‘revolutionary cadres’ could have gone off happily to schools of tactics and strategy in prison or in exile!”

A moral victory of sending lambs to slaughter without ever bowing to our enemies may make one feel better, but it does not achieve much for the working class.

Conclusion

“The history of Communism in the developed economies of the west has been the history of revolutionary parties in countries without insurrectionary prospects.”

Eric Hobsbawm, New Left Review

Beyond simply not having insurrectionary prospects, the history of communism in the cases of France and Italy is the history of parties which never had time to breathe. In barely forty years in the early twentieth century, communists in Western Europe saw a victorious struggle for universal suffrage almost immediately undermined by a world war. This in turn was swiftly followed by a plunge into fascism and a reversal of democratic freedoms, further carnage of communist militants, and the emergence of a new global super-power, the United States, which directed its extraordinary wealth and power towards ensuring communism did not break through in Western Europe.

In this context, it is nothing more than wishful thinking to imagine that, had Togliatti been more or less Leninist, or had Thorez been more or less loyal to Stalin, both parties would have swept to power irrespective of domestic and American opposition and progressed unperturbed towards communism.

In reality, doctrine and ideology are only one small part of the puzzle. Our tactics, the resources – human and capital – at our disposition, the strength of our enemies and, ultimately, the hand which history deals us, have huge roles to play also. To criticise the weakening of the communists by the 1970s as a failure solely or mostly on their part is to ignore the impossibly difficult hand which they were dealt.