When the Bolsheviks seized power in 1917, their goal was not only, or even primarily, to transform the Russian Empire. They aimed to shake the world. The revolutionaries in Petrograd calculated that their revolution would catalyse proletarian revolutions around the globe in a matter of months, if not weeks. For them, world revolution was both necessary and likely. They counted on revolutions in more “advanced” countries to guarantee the success of revolution in “backward”, largely peasant Russia. Their predictions turned out to be wrong, and the Soviet state survived as an embattled fortress of socialism. This turn of events raises the question of how and why 1917 remained a global project, even as it failed to spark world revolution.

Part of the answer lies in the systematic efforts of the Soviet state. When the anticipated world revolution failed to materialise spontaneously, the Bolsheviks moved to institutionalize efforts to encourage it. In early 1919, facing a civil war and foreign intervention, Soviet leaders founded the Third or Communist International (Comintern) as the headquarters of world revolution. Even now, from the vantage of our thoroughly globalised world, the breadth of the Comintern’s revolutionary ambition is stunning; by 1935 it operated on six continents and had a total of 65 member parties. Working in well over a dozen languages, Comintern agents and functionaries collected information and issued directives on topics as diverse as strikes, the organisation of women and youth, eluding the police, the celebration of communist holidays, and the training of new cadres – to provide only a very partial list. The Comintern, in short, can be understood as an enormous fact-finding and revolution-making operation run out of Moscow, structured largely (and increasingly) by the shifting needs and interests of the Soviet leadership.

This understanding of the Comintern as a hierarchical, Moscow-centered institution devoted to exporting the Bolshevik brand of revolution has been extraordinarily influential among communists, anti-communists, and historians of international communism. And it is not incorrect. Recently, however, historians have begun to turn from questions of how much control Moscow actually exercised over national parties to investigations of the ways in which a wide range of individuals turned the abstraction “international solidarity” into concrete realities. It is these individuals, embedded in institutions based in Moscow, but also constructing their own transnational networks, who provide a key to understanding the lasting international appeal of 1917.

Even under Josef Stalin, who tightened Soviet control over the Comintern, it remained a globalised network firmly linked to Moscow but reliant on often personal connections across borders. In the early 1930s, American communist Steve Nelson attended the International Lenin School in Moscow, the Comintern’s most prestigious institution for training foreign cadres. Looking back on his experiences in 1981, by which time he had been a former communist for almost twenty-five years, he fondly recalled “exchanging stories and arguing politics” with his roommates, who came from across the English-speaking world – an Indian who had escaped a British colonial prison, a “working-class intellectual” from Australia, and “some Scottish and Cockney” comrades. Nelson remembered, with perhaps a degree of nostalgia, that these informal exchanges, at least as much as his classes, produced a powerful sense of belonging to “a movement in which solidarity on a global scale was more than an abstraction”.

The Comintern’s influence relied on its ability to foster this sense of belonging. Clearly the Bolsheviks’ status as the makers of the world’s only successful proletarian revolution added to their prestige and authority. It is important to understand that international communists often welcomed guidance from, even subordination to Moscow. Becoming more like Bolsheviks – embracing “iron discipline” and ideological purity – appealed to international communists for whom the Russian revolutionaries provided heroic role models. The point of “becoming Bolshevik” was to be part of a worldwide movement that offered not only the hope but the certainty of a better world. As one American communist who joined the Comintern-sponsored International Brigades in Spain remarked in a letter to his wife: “if a person were not a Communist he would be in despair”.

The question of how the Comintern constructed this sense of transnational belonging remains profoundly relevant. Even with access to internet and email constructing solidarity on a global scale is no easy task. How did the Comintern manage it with letters and telegrams? A close look at communist networks and the people who operated within them suggests the importance not only of shared goals and ideals but also of emotional and cultural ties. Communists created not simply a political movement but a way of life.

Combining the personal and the political did not always draw communists together. Many foreign communists in Moscow reacted with surprise and dismay when their Soviet comrades, ignoring any notion of individuality or privacy, conflated personal shortcomings and political deviance. A Chinese comrade, who observed Klavdiia Kirsanova, the director of the Lenin School, engage in “self-criticism” in 1929 remembered that the foreign communists were “astonished” when “in the course of her hour-long confession she even made mention of her private life during her younger days”. By the late 1930s, when the Stalinist purges decimated the Comintern, such “personal” failings could have substantial, even deadly consequences.

At the same time, the Bolshevik insistence on the interpenetration of the personal and the political could bind the communist community together. Between 1926 and 1938, the Lenin School graduated roughly 3,000 students from fifty-nine countries. Housing international comrades four or eight to a room and giving students free time in the evenings, as Nelson recalled, to sprawl on their beds, tell stories, and argue, the Lenin School authorities created, consciously or not, an atmosphere that promoted emotional as well as political bonding. For Nelson, the emotional solidarity may have been particularly clear in retrospect. He concluded the story of his roommates with the observation “I met some of them again on the battlefields of Spain”, where he saw some of his school friends die.

The International Brigades in Spain constituted the Comintern’s largest and most ambitious, although ultimately unsuccessful, international operation. Over the course of the Spanish Civil War, some 35,000 international volunteers, predominantly communists, joined the fight for the Spanish Republic. Comintern records make clear that there was plenty of dissension, disobedience, national rivalry, and drunkenness among the volunteers. Nonetheless, many who were there – and even many who experienced the war only vicariously through the Comintern or Soviet press – saw the war in Spain as forging and confirming the reality of international solidarity. In their letters home, American volunteers described the camaraderie of the front as both intimate and political. As Ben Gardner wrote to his wife, “Never before did I feel such a deep regard for comrades, especially those who took the fight with a real antifascist and bolshevik stamina”. An anonymous poem submitted to the newspaper of the 15th International Brigade emphasized the volunteers’ diversity:

“Men from the Nazi dungeons,

Scots from the Glasgow slums,

Frenchmen, Dutchmen, Irish,

…

Speaking a score of lingoes,

Dirty and ill-arrayed.”

Yet they were all united, “Singing into the battle” – perhaps the “Internationale,” a song that virtually all the volunteers knew, even if in different languages. In letters and later reminiscences, the fact that the “Internationale” sounded everywhere in Spain served as thrilling proof of international solidarity.

After the fall of the Spanish Republic in the spring of 1939, communists who had fought in Spain maintained their connections to one another through veterans organisations and correspondence networks. Dolores Ibárruri, the leader of the Spanish communist party, who went into exile in Moscow, stood at the heart of one such network. From the time she arrived in the Soviet Union in mid-1939, Ibárruri maintained a far-flung circle of contacts that included Spanish communists in Eastern Europe and Mexico, foreign veterans of the Spanish civil war, and a who’s who of international communist leaders. She often wrote what might be termed sentimental political letters, letters that made little distinction between political goals and personal needs. Ibárruri’s Russian, American, and East European correspondents often addressed her in emotional terms as a “beloved” leader, and she responded in emotional, if also formulaic, language. Her correspondents among the Spanish exiles wrote requesting everything from housing to marital advice. Ibárruri responded with both political and personal guidance, telling one comrade who had asked her to try to effect a reconciliation with his estranged wife that his wife had ceased to love him and that he should look to his “work and the fulfillment of your duty for some compensation for this lack of affection”.

These correspondence networks rooted in the struggle in Spain survived into the cold war despite increasing hostility to cross-border connections on both sides of the iron curtain. In the Soviet Union the so-called anti-cosmopolitan campaign targeted people with international ties, especially Jews. In Eastern Europe, veterans of the International Brigades were prominent among the defendants at the show trials of the early 1950s. This xenophobic atmosphere notwithstanding, Ibárruri maintained her international contacts. In 1952, on the occasion of International Women’s Day, she sent more than a dozen telegrams to communist women in Europe, Mexico, and China. Each message was lightly tailored to the recipient. The note to Romanian communist Ana Pauker, whom Ibárruri had met when both lived in Moscow during the Second World War, emphasized their personal acquaintance, concluding, “I remember you fondly, and send heartfelt greetings on International Women’s Day”. However banal, the greeting went against the tide of Stalin’s growing suspicions of anyone with international connections. Just over a month after Ibárruri sent her telegram, Stalin told visiting Romanian leader Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej to “get rid of Ana Pauker … If I were in your place, I would have shot her in the head a long time ago”. Pauker was arrested in February 1953, but a planned show trial was cancelled in the wake of Stalin’s death a month later.

On the other side of the cold war divide, maintaining international connections was also increasingly risky, although never as risky as in the Soviet bloc. In June 1951, the US government arrested American communist Elizabeth Gurley Flynn for violating the Smith Act, legislation that essentially criminalized the Communist Party. Her arrest did not prevent Flynn from sending a telegram to Ibárruri in Moscow soliciting a “tribute to Mother Ella Reeve Bloor Great working class leader died August tenth”. Ibárruri obliged the Americans with a formulaic but also seemingly heartfelt paean to Bloor’s exemplary “strength and abnegation”. The request and Ibárruri’s willingness to grant it suggest that communists valued such ritual expressions of sympathy and solidarity as a means of building and sustaining an international movement. For imprisoned American communists – Flynn was convicted and spent two years in a federal prison camp – such international support may have been particularly important. Steve Nelson, who served time in a Pennsylvania prison for violation of the state’s sedition law, remembered that the letters he received from all over the world with “warm expressions of affection were wonderfully heartening”.

The networks rooted in Spain remained active, even expanded, in the wake of Nikita Khrushchev’s 1956 “secret speech” that three years after Stalin’s death offered a limited, but still stunning, disclosure of the former leader’s crimes. Both communists who left the party, like Nelson, and those who remained loyal to it, like Ibárruri, worked to preserve and perpetuate the memory of the “good fight” as untainted by Stalinism. In the 1960s, Fredericka Martin, who had served as the administrator of the American medical personnel in the Spanish Civil War, began a massive project to collect information on the international medical volunteers. She corresponded with hundreds of veterans from around the world, soliciting comprehensive accounts of their work in Spain. Nelson supported her efforts, advising in a 1971 letter that asking questions like “Did you really think you could help stop Hitler?” would make the volunteers’ stories relevant to the new left and especially activists protesting the war in Vietnam.

Emphasising the emotional and personal truth of international solidarity involved a large measure of forgetting. In letters, telegrams, and veterans’ organisations, communists preserved their personal memoires of making vital contributions to the cause of “all advanced and progressive humanity”. In the process, they often “forgot” that the phrase was Stalin’s. Nowhere was the forgetting clearer than in a 1977 interview that Ibárruri gave after returning to Spain. A question about the arrests of Spanish exiles and veterans in the Soviet Union drew an emphatic response from the eight-two-year-old Ibárruri: “if Spaniards were arrested I don’t remember. … I don’t remember, I don’t remember, what more do you want?” This is a startling lapse given the number of friends and acquaintances, both Spanish and Soviet, who disappeared in the purges. Such vehement forgetting was the obverse of Ibárruri’s powerful memory of solidarity. In a 1975 letter to Nelson on the occasion of his seventy-second birthday she insisted that “the time and distance separating us notwithstanding, we have not for a moment forgotten the meaning of your participation in the struggle to liberate our people, and feel ourselves forever indebted to you”.

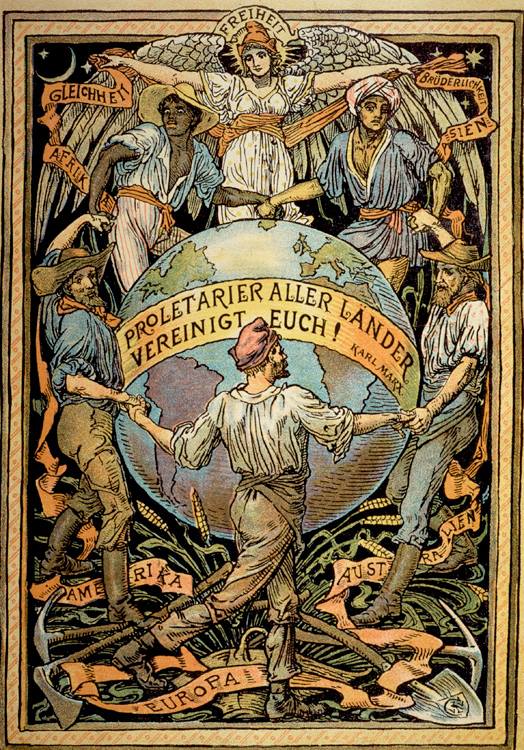

The persistence of such potent and necessarily partial memories can help us understand how communists turned international solidarity into lived reality. A large part of what attracted people to the party – and what the party seemed to have put into operation in Spain – was a solidarity that transcended, but did not efface, difference, that, to borrow Fredericka Martin’s phrase, fostered “the unity of variety”.In their personal networks, veterans endorsed and perpetuated an alternative to the ideological purity enforced by the Stalinist terror. Their desired and remembered communist solidarity was not the solidarity of racial or national purity so prominent in many political movements of the interwar period, especially in Nazism, but rather a solidarity that crossed borders, that embraced border-crossers, outsiders, heterogeneity, hybrids of all kinds. This idealised picture of the cause can be dismissed as a myth or a whitewash. But it also offers a usable past, a touchstone and a resource for others seeking to build a new egalitarian world without borders.