At first glance, anti-imperialism seems to be the kind of ideology everyone would get behind. Most people instinctively don’t like the sound of imperialism— the word carries connotations of the dreadful acts perpetrated by Romans in Constantinople, Crusaders in Jerusalem, or pith helmet-wearing Britons in India. In Ireland the character of anti-imperialism is intimately tied to national identity and liberation from occupying powers. However, imperialism is by no means a thing of the past. Imperialism is alive and well, albeit in more insidious guises.

Empires no longer proclaim their territories; rather the seizure of land is a somewhat more subtle, or even covert, operation compared to, say, the modus operandi witnessed during the nineteenth century scramble for Africa. Even in its cunning contemporary mutations, imperialism may still be readily identified.

What is Imperialism?

Imperialism can be understood in several ways:

Economic historians Gallagher and Robinson have framed imperialism as a political function, not just for the expansion of the economy of a particular region, but also in terms of political and social organisation.

According to Michael Parenti, imperialism is “the process whereby the dominant politico-economic interests of one nation expropriate for their own enrichment the land, labor, raw materials, and markets of another people”. The Parenti definition specifically argues that the nation must play a role in imperialism.

Similarly, Johan Galtung claims imperialism is “a special type of dominance of one collectivity, usually a nation, over another”. Galtung’s definition additionally allows for non-nation entities to play a role in imperialism, e.g. multinational businesses.

Significantly, none of these three separate definitions makes mention of military intervention. This is because military intervention is typically the last resort for empires; it is certainly not always necessary. Imperialism and military intervention are not intrinsically tied together.

If one defines imperialism as requiring military intervention, there are several prominent examples in recent decades, wherein military intervention has been used to seize land, labour, and resources, e.g. the invasion and seizure of oil in Iraq, 2003.

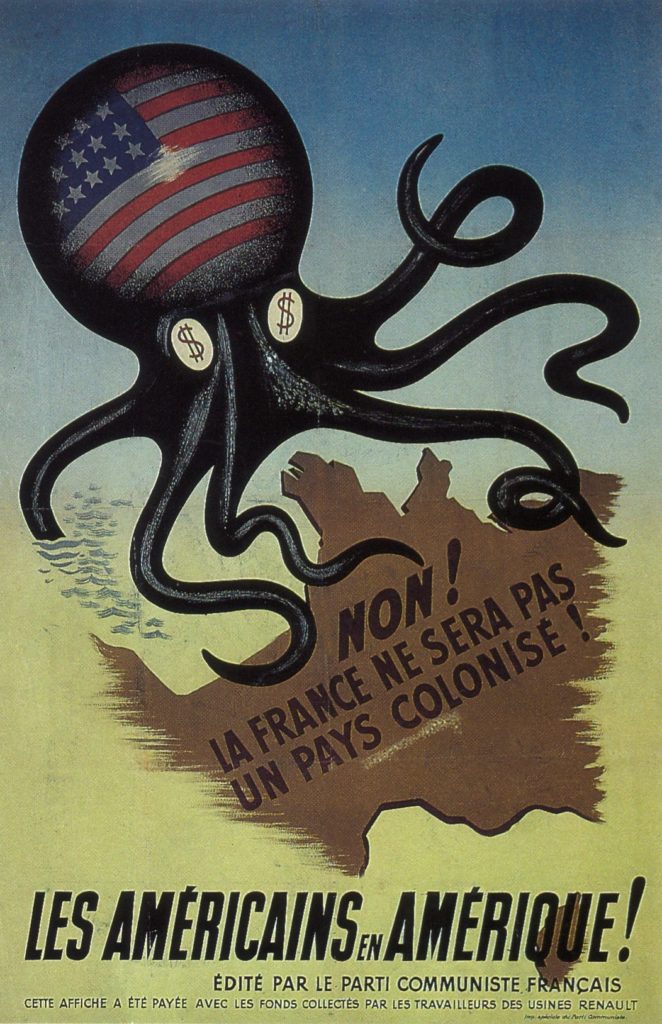

There are, however, many modern day examples of imperialism which require fewer boots on the ground. In Haiti, the minimum wage was dropped to 31 cents an hour because the U.S. undermined Haitian rice production by briefly over-subsidising domestic rice in order to out-price and collapse their market. The U.S. has come to benefit from former farmers who now work in sweatshops and industrial labour. In South Korea, the U.S. forbade the construction of an all-Korean railway. As the U.S. supplements the development of the South Korean economy, the South Koreans, in turn, could not afford to agitate the United States. Pakistan, Afghanistan, Indonesia, Honduras, Columbia, Ukraine, and many more countries must comply with the U.S. out of fear of economic loss, sanctions, or military invasion.

It is not just nations, like the U.S., that are imperialist. Multinational corporations also have the power to exploit poorer countries. Coca-Cola, for example, rather infamously murdered union leaders in South America in order to deter those who would seek a raise in wages. Of course, institutions like the Brazilian government and police are too economically dependent on the revenue generated from Coca-Cola to do anything about the situation. Businesses like Nestlé have worked with the government of Pakistan to privatise parts of the national water works, making the populace dependent on purchasing their water from Nestlé.

To further complicate matters, organisations which have an input into a range of interests, across various nations, can also be imperialist. This includes organisations who have control financially (IMF, OECD, World Bank Group, WTO), politically (EU), or militarily (NATO, OSCE).

These businesses and organisations can rely on nations to pursue military activity. Often, the reason poorer nations comply with U.S. based businesses is out of fear of U.S. military intervention. The historical legacy of direct U.S. intervention, which has collectively left millions dead, in Vietnam, Laos, Grenada, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, Panama, Somalia, and Yugoslavia, suffices as enough of a threat to the rest of the world.

Thus, it is more accurate to say that imperialism is an unequal relationship between nations, in which businesses and organisations can play a significant role. A number of different entities can be described as imperialist, but the aim is still the same: to exploit and deliberately deter development in another nation, in order to create a dependent relationship.

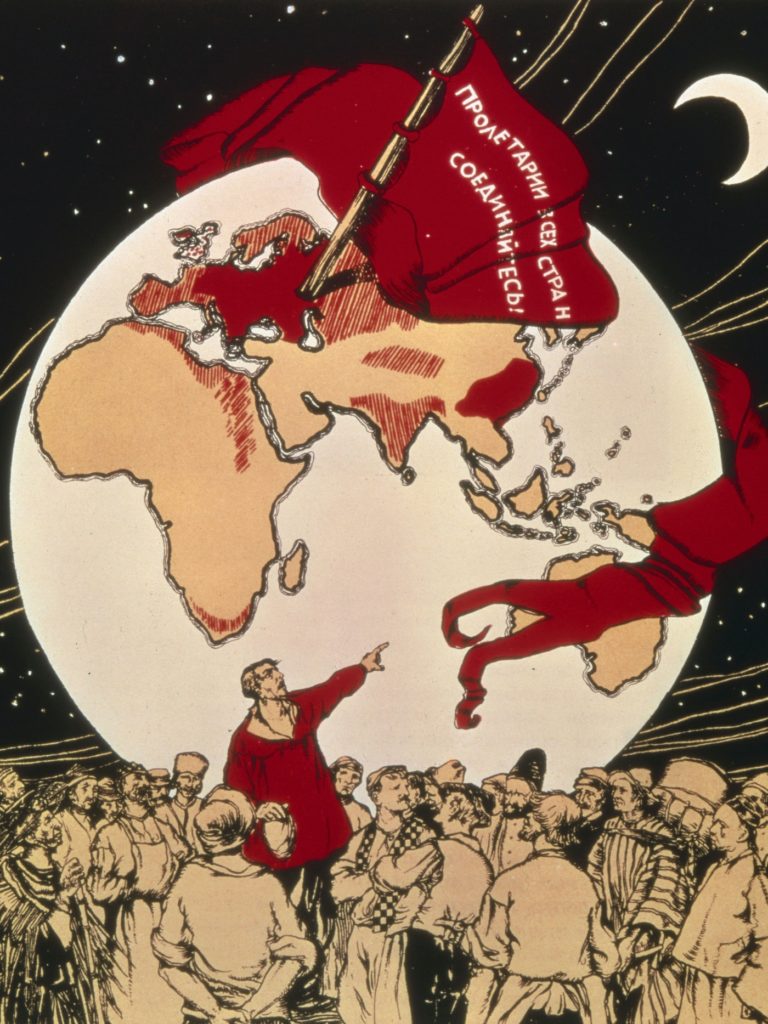

Anti-imperialism is the opposition to such practices of imperialism and, in theory, offers a complementary support for the independence, sovereignty, and right to self-determination of all nations. Anti-imperialism calls for the liberation of all oppressed peoples.

Anti-Imperialism

How does anti-imperialism play out in practice?

Anti-imperialism is not as easy a position to maintain as one may think. To vigorously defend anti-imperialism is often to defend nations and cultural values that one would otherwise find abhorrent. In the face of imperialism we instinctively ought to support the people who are suffering as a consequence of imperialism. This is not the same as supporting the leadership of an affected nation for its own sake; it is rather a cognizance that the exploitation of a people will worsen under an imperial power.

Thus, it is the case that when presented with material conditions unfit for proletarian revolution—that is to say, when we are unable to contemplate ideals in the face of a difficult reality—we must ask, who the main benefactor will be?

Who benefits? Will the imperialist forces benefit, or will the people benefit?

If nothing prevents the imperial powers from benefiting, we must resign ourselves to the fact that, until the imperialists are gone, the people will not be safe to liberate themselves. As such, we must support the presiding power, even if it is bourgeois, for we must accept that the land-grabbing policies of the imperialists will leave the people without resources, protection, and economic security, making for a dog-eat-dog scenario amongst the people.

All too often there is talk of alluring third position, which oppose both the imperial powers and the domestic government in favour of the ambiguous entity known as “the people”. However such a position only serves to abet the aims of imperialists, as it does not offer concrete solutions or a blueprint for actions to be undertaken. As such, these neutral, moderate or third positions have nothing to offer the troubled nation.

For Marxists, particularly Marxist-Leninists, the struggle for nations to gain sovereignty by wresting it back from those imperial aggressors who wish to exploit the nation requires unwavering attention. Marxism–Leninism has long spoken of the need to support oppressed peoples, even when the struggle is bourgeois anti-imperialist in nature, as there can be no greater oppression than that of empire. It is only when a nation is free from imperial powers that it may begin to flourish, providing conditions conducive to the rise of the class-conscious proletariat.

We can look to Ireland as an example of a loose coalition of socialists and bourgeois nationalists, who joined forces to fight against the British Empire in the Easter Rebellion of 1916. It was as necessary then, as it is now, that national liberation becomes the principal focus of revolutionary activity while under imperial occupation. The assistance of the national bourgeoisie is required and useful in such circumstances. One must end super-exploitation before one gains the power to end exploitation as such.

One might argue that foreign imperialists and the national bourgeoisie are of the same class, and that is certainly true. However, to say that all sections of the bourgeoisie are on equal footing, or more accurately, that they are all equally problematic for the working class, is dogmatic and misses the point. There is uneven development even amongst the bourgeoisie. The national bourgeoisie are always more than happy to end their own subservience to the imperial bourgeoisie.

It should be noted that one need not be a Marxist to oppose imperialism, as demonstrated in 2018 when many libertarians and conservatives called for an end to war in Syria and Yemen. While this may have been for very different reasons, one can appreciate allies of anti-imperialism regardless of their other beliefs. Conversely, there has historically been a grouping of idealistic socialists who believe we can support a third party; one can support neither imperialist nor bourgeoisie. However, in reality this hypothetical revolutionary group capable of simultaneously ending imperialism and capitalism do not appear from the mist.

Many who claim to support anti-imperialism are often the first to the defence of imperialists calling for a humanitarian intervention to “save the people”, “end dictatorship”, or “stop terrorism”. Unfortunately, these humanitarian interventions are very often a pretext for imperialism, not against it. The events concerning Yugoslavia throughout the 1990s demonstrate this very well.

While anti-imperialists should be critical of these kind of humanitarian interventions, there is a questionable tendency to condemn all military interventions without a suitable analysis. Indeed, when one reviews the history of U.S. ‘humanitarian’ intervention it becomes evident that the humanitarian aspect of such military operations is rather absent. However, to reject humanitarian intervention as a legitimate tool for political aid ignores the many countries that have intervened for the benefit of the nation. Thus, we should ask: when is humanitarian intervention legitimate? Can military intervention be anti-imperialist?

Military intervention can only be legitimate when it is not imperialist; only when intervention struggles to assist the self-determination of a nation without gaining influence over the political and economic functions of that nation can it be considered anti-imperialist.

For example, when the French assisted the United States during their revolution against the British, the French did not benefit materially in terms of the definition of imperialism outlined above. This can be a considered a legitimate anti-imperialist military intervention. As a counterexample, when the US bombed Yugoslavia in 1999 for the purpose of creating the client statelet Kosovo, that was not a legitimate military intervention but rather a case of imperialism.

While many argue that organisations like the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) have the ability to grant the right to intervention, we should remember that, as discussed earlier, an organisation can be imperialist. Given this fact, it seems unreasonable to assume that the UNSC could be exempt from the status of imperialism. Thus, the aforementioned criterion remains the most appropriate tool of analysis, as it raises the question of legitimacy according to circumstances, not the agents involved.

The case for anti-imperialist military intervention, and its proper role within anti-imperialist struggle, is best illustrated through the examples set by the German Democratic Republic (DDR) and the USSR.

The DDR and Southern African Nations

Anti-imperialism was at the forefront of DDR foreign policy. As a Marxist nation facing the threat of war and annexation from the neighbouring Federal Republic, solidarity with other nations who struggled for liberation was a logical move for the DDR. Politically, the DDR needed recognition and allies from the international community if it was going to survive. As the Federal Republic immediately ended relations with any nation that recognised the DDR as a state, political allegiances to either Germany were reduced to a binary.

The DDR sought out relations with African nations in the wake of the anti-colonisation movement in the 1960s. The DDR was one of the first states to support the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa in the early 1960s, even partaking in boycott at an economic loss to itself. The DDR made allies with Vietnam, Angola, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, and later Zimbabwe. As the DDR was not as wealthy as Western nations or the USSR, the support the DDR offered was seldom economic and almost always political.

The DDR often sent volunteer youth brigades to assist the building of infrastructure, and medical teams to war-torn countries like Vietnam, Angola, and Mozambique. The DDR also established a program for those in colonised countries to receive free education and professional training in the DDR.

Additionally, it provided logistical support and training for SWAPO, the movement for independence in Namibia, and ANC in South Africa. In fact, the DDR was responsible for printing Sechaba, the official ANC newsletter. These often one-sided relations between the DDR and the former colonial benefactors demonstrate a rigid commitment to anti-imperialism by the German state.

In terms of military intervention, the DDR played a crucial role in supporting the MPLA of Angola and FRELIMO in Mozambique. Both civil wars ended with the victory of the socialist governments as opposed to reactionary forces who sought to divide the countries. While one could assert that it was in the interest of the DDR to protect these socialist governments to preserve trade partners, that hardly seems to satisfy the criterion of economic expansion. Furthermore, the DDR was not the only intervening army during the Angolan and Mozambican civil wars. When we consider that countries like the U.S., Zaire, South Africa, Israel, Rhodesia, and China were weighing in to overthrow progressive national liberation movements, it doesn’t take a lot of imagination to figure out how those countries would have benefited. Angola and Mozambique exist as independent nations today in no small part due to the anti-imperialist efforts of countries like the DDR.

In both cases, the USSR and Cuba, especially in the case of Angola, made great sacrifices for the preservation of socialist states with no material benefit to be claimed for themselves. In fact, often these socialist countries protected each other at great economic cost to themselves. The USSR military intervention is a prime example of a lengthy war that ended up costing the USSR billions.

The USSR in Afghanistan

After a successful revolution in 1975, Nur Taraki and the Marxist PDPA government in Afghanistan legalised unions, set up a minimum wage, a progressive income tax, a literacy campaign, and greater access to healthcare, housing, and public sanitation. The government then proceeded to give women education, introduce a land reform campaign, and eliminate opium production. This was met with serious opposition from fundamentalists, landlords, and opium traffickers, who then executed Taraki, on the order of Foreign Minister Amin, with the help of the CIA.

After eleven requests from Kabul, the Soviet Union intervened, killing Amin and reinstating the PDPA under the leadership of Babrak Karmal. The USSR fought for a full decade to assist and preserve the PDPA against the barbaric Mujahideen who sought to install a reactionary Islamic state. As the USSR was wealthier than other anti-imperialist nations, such as the DDR, it could afford to offer military support for many years. However, with the arrival of Gorbachev in 1985, major reforms were made in Soviet policy. Gorbachev withdrew Soviet forces from all over the world, including from Cambodia and Mongolia. Ultimately, Gorbachev’s political maneuvers cost Afghanistan the war by 1992, letting it fall to the Mujahideen. Nevertheless, we can praise the efforts of the USSR to preserve the national sovereignty in the name of anti-imperialism, unlike the US, who today is failing to keep the NATO-backed Mujahideen in power in the face of the more powerful Taliban.

Conclusion

When we understand that imperialism is alive and well in the modern world, we must also grasp the importance of anti-imperialism. On its surface, anti-imperialism appears to be a relatively simple position; but without the imperial self-declaration and hubris of the past, it becomes difficult to locate our solidarity with such a cause. Hence, anti-imperialists must remain vigilant and understand that any nation, business, or organisation can promulgate imperial interests.

Furthermore, we all need to be aware that upholding an anti-imperialist position means lending solidarity to nations that we may not agree with in other regards. Moreover, we should remember that not all military interventions are illegitimate. On the contrary, as demonstrated by the work of the DDR, military intervention can lie at the crux of national liberation and anti-imperialism. Ultimately, anti-imperialism and military intervention are not strange bedfellows—rather, the latter is a crucial tool to be used against the imperial powers that be. The legacy of anti-imperialism in socialist countries is a proud one and we should all celebrate these victories.