When it comes to organising, progressives don’t need to reinvent the wheel – the mass workers party is the only vehicle that can bring us to socialism, argues James O’Brien.

As everyone will know, most political activity is day-to-day work. Writing up a leaflet, booking rooms, attending meetings, keeping up contacts, visiting pickets, supporting campaigns. So it’s good sometimes to take a step back and look at the bigger picture.

What I want to do here is outline in a very simple way our reasoning for doing all that day-to-day work. To start, it’s always worth asking “what is the job to be done” before we select the tool to do it. That is, before we know what a useful strategy is, we need a clear idea of the goal. At the most general level, we can say it’s to create society in which each human can live a flourishing life to their full potential.

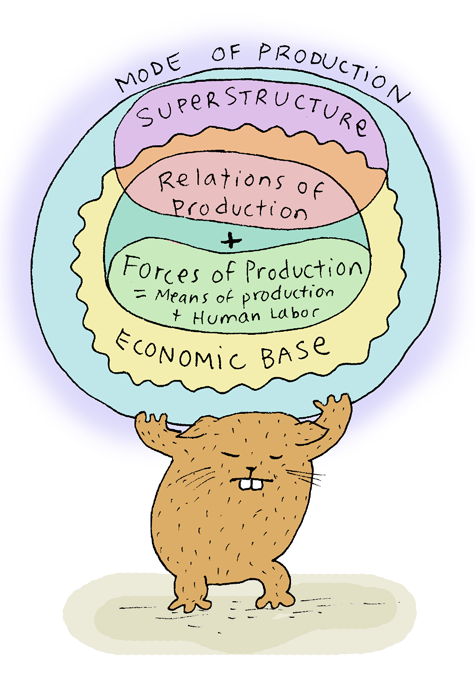

As socialists, we think that instituting co-operative or socialist economy to replace privately owned businesses is necessary to create the structural conditions for that flourishing to occur. This is not just a question of getting rid of poverty. Economic inequality provides the structural resources for other forms of social inequality such as racism. You don’t necessarily solve racism by solving economic inequality — sectarianism is still a problem in the North even as unionist control of industry has declined. But it does make the job a lot easier if you knock out the material incentives and structural supports for them.

So, economic equality is a goal of ours and socialist or co-operative production is a central goal in achieving that. Obviously, it is not the only one. We also subscribe to basic republican goals like civic equality, freedom to organise and so on. But the focus on common ownership of production is what is distinctive about socialism.

What, then, do we need in order to achieve a co-operatively organised economy?

As Marxists, as opposed to liberal leftists or ethical socialists, we place our bets on the working class; that due to its social position and the effect of class struggles it will develop the power to take over and socialise the economy. But how is that to be done?

Social power, labour and political organisation

Here we need a very quick digression on the subject social power more generally. Power is a slippery concept. One way to conceptualise it is as the ability to command labour. Labour is the expenditure of human effort. There’s only so much of it on the planet and if you or your group can mobilise labour you get to do lots of things, everything from constructing infrastructure to waging war to engaging in art to political activism. And every bit of labour that a group controls is labour that is denied to other groups. Since labour is needed to do anything at all there will be competition to control it. In that competition, social groups will prove to have an advantage over individuals and so they will tend to emerge and engage each other in competition. It is a theory of natural selection applied to the social realm if you like.

In our era, certain methods have proven to be extremely good at organising labour: namely capitalist social relations. Not every method is capitalist. Volunteering with a charity isn’t, nor is political activism or domestic labour. But capitalist production is the sun around which all other forms of social life must orbit.

To return to the question of workers instituting socialist production, we can, on this model of a universal competition between groups for labour, say that the working class can only succeed if it can control more labour than rival groups, i.e. corporations and state bureaucracies. Now capitalist corporations are not informal groups. They are not vague networks. Nor is the state bureaucracy organised according to a vague network. They are highly structured formal organisations. And that is no accident.

In order to mobilise the labour of thousands and even millions of people, formal organisation is required and doubly so when we want to engage in constructive work such as running an economy or social services. Destructive work, such as mass mobilisation to bring down a dictatorship can sometimes get by on spontaneous networks. But we are interested in building a new society, not just in tearing stuff down.

The necessity to create formal organisations capable of scaling to a massive level is why an emphasis on movementism, e.g. Occupy, can never lead anywhere despite the freshness and energy with which they start out. At some stage they have to be constituted as actual organisations, and that transition is rarely an easy process. And if they don’t do it, they will fade away.

The workers’ party

But if formal organisation is necessary it is still not obvious that political parties are the best way to change society. There are trade unions, churches, charities. So why do we choose political parties? The short answer is the need to win state power for the working class. Only the state has the ability to both resist a counter-attack from the elite when socialisation is undertaken and only the state has the ability to command enough labour to really socialise the economy in the first place. So the working class needs to win politic power and the primary way of doing this is through political action.

It is not the only way: a lot of people in the early socialist movement, most notably Babeuf and Blanqui, thought they could win political power through military conspiracies. The classical anarchists, on the other hand, when they weren’t terrorists, abjured political action altogether and thought that working class power could only be built via trade unions with the aim of collapsing the state in an insurrection and then using the trade unions to run all of society in their place. Because they wanted to destroy the state they boycotted politics and therefore political organisation.

But our approach is to use politics as a way to win state power and, more precisely, to build organisations capable of wielding it.

The capitalist elite like to keep as many affairs out of the political sphere as possible as they are stronger economically and naturally prefer everything decided by the market. This is no accident as it is through politics that the working class can advance its interests. The more issues that the ruling class keep out of politics the harder it is for workers to win concessions and to build a movement. We want to do the opposite, to bring as many issues as we can into the realm of politics and as working people are the majority the more that issues are subject of politics the better for us. And while trade unions can and do win gains for workers by reducing the amount of a firm’s income going to profits and passing it to workers as wage increases it is through political action that society wide measures can get enacted: e.g. holiday pay, maternity leave, environmental controls.

Because workers lack any productive property, there is little incentive for them to pursue individualist solutions. Whereas the peasants of the past might long for a plot of land, there is no prospect of a worker getting a small bit of a company that he can live off. Worker organisations therefore tend to be fairly socially minded, pushing for collective solutions to social problems: public health care, social welfare, unemployment benefit, social housing etc.

The endpoint of the collectivist measures is, of course, socialism. But if the worker organisations lean in that direction, the pressure of conforming to “being realistic” , makes it very slow to realise its own inherent dynamic. The labour movement does not exist in splendid isolation; it exists in societies which subject it to a lot of pressure to conform and many of them do. Even ones which start off as radical socialists, such as the German SPD end up integrated into the system. It happens right down to our own day, for example the likes of Syriza and of course the Democratic Left split.

But there is that second dynamic to the politics of the workers’ movement, the one that pushes the inherent collectivism to its logical conclusion. It’s not just about securing the welfare of workers within capitalism; it’s about replacing capitalism with society based on socialised production: communism. We tend to think of socialism as being intrinsically connected to the labour movement and get annoyed when Jack O’Connor or Brendan Howlin whoever isn’t a modern day Lenin. But, as we have seen, there is a major tendency within the labour movement to keep it pragmatic, to focus on winning concessions from capital.

This shows I think that socialism and the labour movement are are not automatically going to be united. For sure, they are compatible, but the match still has to be made. And, in fact, even in the 19th century they were originally separate. One of the major innovations of Marx and Engels was to say that socialists had to merge into the labour movement and stop being isolated in small groups.

Trotskyism – ultra-left isolation from the working class

Some socialist tendencies deliberately maintain the separation of the labour movement and socialism. Trotskyism is one. Traditionally they have preferred to retain the purity of their politics and, when revolution arrives, be in a position to assert their political line, so instead of a mass workers party they advocate a small revolutionary socialist party, a sect, and workers’ councils.

In non-revolutionary times, their primary role is to orbit around the major workers’ organisations and act as a critical voice.

Because of their separation from the labour movement, Trotskyists can and do take very idealist positions, such as calling for general strikes without any consideration of how that will work in practice. They don’t have the responsibility to the members nor the interest in building the organisations since it runs counter to their strategy of having small pure organisations.

On the face of it, the refusal to merge into the labour movement is a reasonable position given the propensity of mass parties to become integrated into the status quo. But it is doubtful whether the workers’ councils are up to the task of governing society. Society is very complex and taking over the task of constructing and running a state from scratch, in the midst of a revolutionary upheaval is unlikely to succeed. Even in Russia, which is usually held out as the prime example of where something like this occurred, social control had to be taken by the Bolshevik Party. After about 1919 we hear very little about the soviets.

Orthodox Marxism and the merger of socialism and the workers’ movement

And, in fact, the separation of the masses and the socialism was not and is not the orthodox Marxist position. The orthodox approach was to create mass parties, with a huge membership, which were imbued with a scientific socialist ideology so that could act as a vanguard for the wider class. There were a number of reasons for this.

Firstly, the aim was to educate workers about how society worked and the socialist alternative. You can’t do that from afar and by preaching to them from on high. You have to be with them if they are going to listen.

Secondly, large numbers gave the organisation credibility in confronting its political opponents.

Thirdly, it gives it resources: both volunteer labour and money to pay for professional organisers.

This allows it to plant roots in every street and every parish. Not only do we have the infrastructure to spread our message, we also get feedback from the people on what the problems affecting them are and if our policies and political tactics are useful to them.

A mass party can’t just dictate to the people; it is has to be in contact with them and bring them with it. The question of scale is vital here. The major avenue for advancing socialisation is the State. It alone has the resources and the ability to be the vehicle for the popular will, to do the job of socialising the economy. So, it’s not just for reasons of useful reforms but for the fundamental job of transformation of the capitalist economy into a socialist one that a party is needed.

The importance of scale becomes clear if we consider the job of subordinating the state to the wishes of the majority. It is well known that the upper layers of the state bureaucracy are given to co-operating with the elite. Unless there is a large amount of public pressure exerted on the state it won’t be possible to resist that, let alone get rid of them and replace them with competent people. That public pressure has to be organised both within and without of the state if it is to be a long-term phenomenon.

The abolition of the water charges has shown that the state will bend if enough pressure comes on. But ad hoc movements like that are rare diamonds. Transformative change requires a lot more pressure for years, if not decades on end. Nor can that pressure be focussed on just one issue at a time. There is a lot wrong with this country and so a lot to change. There’s childcare, the health system, education, and housing to name just the most basic issues.

Moreover, even though the Irish state has largely removed itself from active production, we most definitely want to use it to take over as much as the productive economy as possible. This requires gaining control of finance, setting up our own banks and ensuring that officials are not just funding their own boys.

The state, then, is a large and very complicated machine. Directing it towards being a vehicle for social transformation is no easy task. It requires a large and experienced organisation. It’s not a job that can be done on the fly by newly created institutions, like community assemblies. Nor is it a job that can be done by a few socialist intellectuals, no matter how correct.

It can’t even be done by a mass labour movement, if that movement is not animated by the aim of communism. It requires both the labour movement and a socialist ideology. It is only when the two of them merge that they gain the strength to seriously challenge the capitalist order, on the one hand the organisational experience and on the other knowledge of where we want to go.

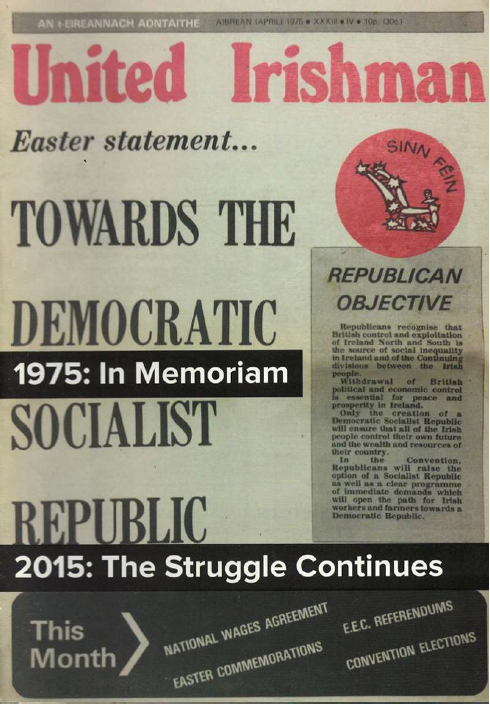

Our present situation in Ireland is that there is a labour movement and there are socialist parties, including the Workers’ Party. But unlike with the original Social Democrats of Lenin’s time or the later Communist Parties we are separated from the labour movement.

It is obviously bad for us since it means we lack the scale and resources to make the impact we want. It’s also bad for the the trade unions since a strategy based exclusively on pragmatism means that they constantly placed on the defensive. The ruling class aren’t too worried by trade unions on their own. They definitely like the extra profits that come from destroying unions and forcing wages down. But ultimately they can live with them. And the ruling class certainly aren’t worried by revolutionary communists on their own. It is only when the two merge into a large mass socialist organisation that the ruling class get scared. The crucial point to note about the merger formula is that they were unitary organisations comprising the convicted socialists and masses of workers.

Strategic Flexibility

There are very few political prescriptions in Marxism. It doesn’t say that violent revolution is inevitable or that electoralism is the only way to victory. It examines the conditions of society and attempts to work out the best forward for that society. But it might be different somewhere else. Of course, the bedrock of socialist politics is class politics and the drive towards collective solutions. How these play out in each country is never predetermined from what happened in another country or in the past. For sure, we can learn from the experiences of others, but to simply copy their approach because it worked for them is a recipe for failure. We have to develop appropriate tactics for our situation.

There are three simple points that I’d like to finish with regarding Marxist strategy. They’re fairly general.

The first is to be in contact with the people and to agitate alongside them. There is no possibility or winning popular support without that.

Secondly, we try to use both existing institutions and policy development to crack open the contradictions within the present system. The Workers’ Party’s Solidarity Housing proposal pushes a collectivist solution that puts the other parties on the back foot. So although we do think we need socialism, that’s not all we have to say. We need to be able to prove to ordinary people that we have policies that are sensible and can make their lives better. If they are implemented we’ll gain support and if not they are useful propaganda in spreading our message of how society could be. The same goes for institutions like the council or parliament. They’re far from perfect, but they can be used to further our message and build our organisation.

Thirdly, I would suggest that a strategy of patience and of building to take advantage of conditions is a hallmark of the successful Marxist parties. We can’t say exactly how those conditions will play out but we do know that there are inherent contradictions within capitalism that will give rise to opportunities. Our job is to build organisations that can take advantage of those contradictions when they arise. This isn’t just a question of waiting in the long grass but of educating our members politically, spreading our ideas amongst the population, developing policies that can help solve the problems that people face, and, of course, having an organisational presence across the country so that we can advance when the tide turns in our favour.

James O’Brien is a member of the Workers’ Party Ard Comhairle.