The role of elections in socialist strategy

The Legacy of the Republican Congress

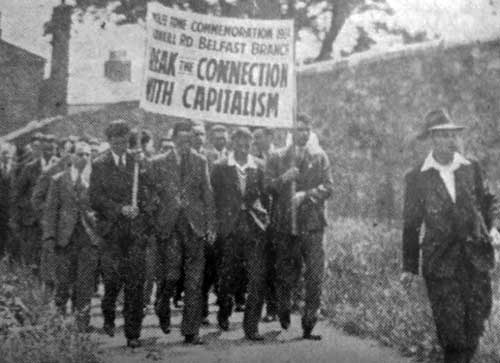

In 1934, in the shadow of a rising fascist threat in Europe, the Republican Congress was convened. This congress brought together the main elements of socialists, communists and progressives, largely drawn from the republican movement. In the few years of its existence, the Republican Congress was surprisingly successful in organising political rallies, pickets, and trade union support, especially given the condition of Ireland as a young post-colonial and underdeveloped state in which it arose.

Ireland was highly socially conservative, had a relatively small working class, the socialist movement was young and the workers’ movement had yet to achieve the kind of mass successes it had won in mainland Europe and in the UK. It would be fair to say that the terrain of struggle was difficult.

The Congress constituted itself as a federation of groups which attempted to work together towards a common cause. However, a motion was put forward that it should constitute itself instead as a political party. This motion was voted down fairly narrowly in favour of remaining as a broad front united against reactionary forces and the rise of fascism. Within a few years, the Congress itself dispersed, breaking up into constituent groups with many participants simply drifting away.

One of the groups involved in the Republican Congress, which actively promoted the position that it should remain federal, was the Communist Party of Ireland (CPI). This orientation in the Communist Party, but also more broadly in the socialist and republican movement, has remained fairly consistent, as we can see from the more recent attempts of the “Peadar O’Donnell Forum” to establish a similar federative network. Peader O’Donnell was himself a member of the Republican Congress and an advocate of this strategy.

With respect to the elections, George Gilmore, a prominent member of The Republican Congress, put forward the following view:

“If in the course of the various struggles that make up the Congress activities – the struggles of the landless men of the framing population for land, of the unemployed for work, of the town tenants for reductions of rack-rents, of industrial workers for better conditions of life – if in connection with any of these activities some person, who has become prominent in the fight, should be put forward as the candidate of whatever party or league or group is making that fight, then I believe that the Congress would urge its supporters to vote for that candidate in preference to any other.”

That is, the Congress should not constitute itself as a party and run candidates, but could tactically endorse candidates of other parties (or independents presumably). This position is remarkably similar to the position held by the CPI (and its affiliated Connolly Youth Movement) today. In the local and European elections of 2019 the CPI, in their periodical Socialist Voice, called for support for independent community candidates but did not advance any candidates itself.

It should be understood that the orientation of Gilmore arises from a context in which Sinn Féin and republicans in general had widely viewed the parliaments in the North and in the South of Ireland as illegitimate or “enemy” parliaments, whose sovereign power they refused to consumate. The contemporary Sinn Féin goes much further than this claiming that participation in the elections, North or South, is outright treason. The Republican Congress position therefore handily avoids being too tainted with the “enemy parliament”, while not completely ruling out tactical flexibility.

The route to power seen by George Gilmore for the congress, is in the organisation of Workers’ and Peasants councils. These councils would grow to become a parallel administrative state which would assume to organs of power, first as a dual power, and finally as the sole legitimate power. The strategy is essentially that which was embraced by the Dutch-German council communists of the 1920s and 30s, and has as originating template, the Russian revolution, in which the slogan “All Power to the Soviets” invoked that legitimate power should go to the workers’ and peasants councils which were formed in the revolutionary climate of 1905 and then revived and ultimately (though briefly) assumed power in 1917.

Hence electoral activity was seen not only as suspect by members of the republican movement, many such as Gilmore saw it largely as a distraction from the building of this more serious and much more important counter-power.

The Balance Sheet

The call to cooperation or federation around a set of principles is always an easier goal, and therefore tends to be “an easy sell”. It is daunting to attempt to fuse people into a united organisation, with all of the organisational and ideological differences which exist in their respective parts. Faced with seemingly insurmountable difference, the easy option is a looser affiliation.

What is loosely bound, is also easily untied. And so it was with The Republic Congress which managed to hold together for only a few years. Having produced the first sizable socialist and republican movement in Ireland’s history (The Fenian proclamation is an amazing document, but it’s arguable how widely its sentiments were actually felt) the Republican Congress participants can hardly be blamed for this fate.

And though there was briefly a progressive party, Clann na Poblachta with some popularity, a socialist party with the aim of organising a workers movement, and some success in doing so, would have to wait until the socialist turn in the republican movement which led to Official Sinn Féin, later the Workers’ Party.

The Workers’ Party’s history is not without its complicated twist and turns, its character being reinforced by the Provisional split of those dissenting from the “political turn” which the majority leadership of Sinn Féin endorsed, coupled with the opening up of a serious conflict in the North ultimately caused by remaining juridical and economic sectarian divisions imposed by the British state.

The strategy of shifting the republican movement to a socialist orientation, merging the republican movement with the labour movement, and both taking part in elections and extra-parliamentary struggles resulted in a scale and duration of class conflict which has not yet been repeated. While the Workers’ Party of the early 80s could boast 1000s of members, many dedicated socialists who had been educated about Marx and class dynamics of capitalism, the alternative socialist strategies along the lines of those outlined by the Republican Congress, despite being pursued actively by various groups, including he Communist Party of Ireland, have failed to gain any significant purchase.

It must be acknowledged that the Workers’ Party had itself serious mistakes of orientation, political errors and dubious self-promoting characters rising to prominence at various times. Though steps can and should be taken to prevent such occurrences in the course of the development of a party, they are a danger that rises proportionally to the size and importance of a party movement. The small can remain ideologically pure and untainted by dangerous missteps, but no party of capacity can do so indefinitely.

The point is not however to justify this or that position of the Workers’ Party or to denounce those positions of the other groups in the various complex terrains that arise in political reality in the course of class conflict. Rather it is that the general strategic approach found purchase in mass activity and mass support by the working class, while its counterpart, the “council communist” strategy did not.

The Strength of Antiparliamentarism

While conditions of social and political economy deeply shape which strategies are available to socialists and the exact context must be carefully taken into account, the extra-parliamentary strategies of syndicalism and council communism, irrespective of their political nuance, have proved vastly less effective in the much broader field of Europe. This is true in scale and impact in the context of even very limited democracies, and certainly in the fully developed western bourgeois democracies.

No socialist political movement has taken power in a fully fledged democracy, by any strategy, leaving us with a paucity of statistical examples of successes and complicating the analysis. However there have been some near misses. Immediately after WWII the US conspired with local bourgeoisies to suppress communist forces, holding off elections in France and Italy until they felt non-communists forces were safe. In Chile, Allende attempted to implement socialist measures which were forestalled by a coup in cooperation with the CIA.

And while communist parties such as the PCI in Italy, the PCF in France and the KKE in Greece gave rise to movements of 100s of thousands or even millions, the council communists and syndicalist impacts were far more limited. And the record of Venezuela is not yet set in stone.

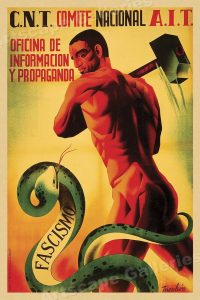

Among the most impressive examples of extra-parliamentarian political formation is the CNT (Confederación Nacional del Trabajo) of Spain, which managed to pursue a syndicalist strategy which genuinely became mass. Yet this was in a context of a very young republic which was almost immediately destabilised by a reactionary putsch. And ultimately they found themselves taking part in elected governments.

Of the more Marxist “council communist” approaches the Kommunistische Arbeiter-Partei Deutschlands (KAPD) is notable. It had not only a party dedicated to education but also associated unions and even at certain points, paramilitary forces.Though itcould count its support in the 10s of thousands these numbers were directly inherited when it split away from an electoral formation. It then proceeded to almost immediately lose 90% of its members, returning to the size of a sect before disappearing entirely.

Similarly, the Italian wing of council communism, of which Amadeo Bordiga was an important proponent, ended up drifting into microgroup obscurity while the Italian Communist Party was giving the US securicrats in NATO and the CIA nightmares.

The council communist idea is inspired by the events of the Russian revolution, where the soviets represented a dual power, that eventually superseded other governmental organs. Yet the Bolsheviks, which became the motive driving force of soviet supremacy did not achieve power by a slow process of building councils over decades. Instead they built a social democratic workers party (RSDLP) over the course of decades, which involved itself not only in union activities, media, community organising, but also every democratic outlet available to it, including the decidedly undemocratic Duma.

“Soviets”, which might also be called “councils”, arose as a response to the revolutionary conditions of 1905 and then resuscitated themselves during the increasingly revolutionary conditions of 1917. It was only in this later phase in 1917 that the Bolshevik party decided that they should be the vehicle of proletarian power. To imagine that we build the soviets first, and the party will follow is to invert the causal direction of the exact historical referent from which council communism arises.

It was precisely to dispel this “council communist” confusion that Lenin decided to write his famous work “Left Wing Communism: An Infantile Disorder” in the 1920s which was directed at the Dutch-German council communist trend and its advocates. And while Lenin was very much an advocate of base building, advancing the unions, etc. He was quite hostile to the idea that action should only happen “from below”:

“The long reign of political reaction in Europe, which has lasted almost uninterruptedly since the days of the Paris Commune, has too greatly accustomed us to the idea that action can proceed only “from below,” has too greatly inured us to seeing only defensive struggles. We have now, undoubtedly, entered a new era: a period of political upheavals and revolutions has begun. In a period such as Russia is passing through at the present time, it is impermissible to confine ourselves to old, stereotyped formulae. We must propagate the idea of action from above, we must prepare for the most energetic, offensive action, and must study the conditions for and forms of such actions.” – Two Tactics of Social Democracy, Vladimir Lenin

The Theoretical Structure of Electoral Necessity

The historical record does not paint a favourable picture of the extra-parliamentary approach, but it is important to make a theoretical examination of why this might be the case. We will restrict ourselves to investigations of the developed western democracies, of which Ireland is a special case, in order to narrow the field.

The primary reason that elections must necessarily be a core activity of the party pursuing socialist transformation is that, contra strategies of the ruling class, the socialist transformation requires politically directed activity, expressed in a programme and propelled by mass activity. A very substantial fraction of the population must be directly involved in the organisation of this programme and organisational activity, and an even larger fraction should be either sympathetic, or at least not functional antagonistic. Without these factors, success is impossible and failure is assured.

Elections give a forum in which to involve members in presenting a program to the broader population, and a means of assessing where it is we stand vis-vis this population. The micro-group eschewing elections can always imagine its reach further and its message deeper, but those who take part in elections have a much more demonstrable measure of the reality.

And while it is certainly possible to pursue the politicisation of the unions, community groups, etc via a political party which does not involve itself in elections, the unions, community groups, etc. will consistently look to the political representation when it comes to issues of importance on the day. When the extra-parliamentary party calls for reforms it can not enact, and the union turns to the left-wing of the neoliberal establishment, is it really the union who is to blame?

And so it is that these extra-parliamentary groupings find themselves engaging in normal union activity, periodic spontaneous resistance, and the occasional stunt, yet amount to little more than ginger groups for other left wing parties and independents in the best of cases, or simply as gadflies denouncing the activities of those who engage in electoral activity at the worst. The halfway-house of the republican congresses “tactical support” is similarly no antidote. It serves only to cede the territory to other actors in the electoral arena, which it finds itself either denouncing, ignoring or tailing and these other political actors have little reason to seek approval or support in return.

By contrast, even very marginal activity with a radical message in elections tends to reconfigure the playing field. The Workers’ Party, with only one member on Dublin City Council put Sinn Féin under a large amount of pressure, limiting their capacity to liquidate public assets, and forcing their votes to the left. The promotion of public housing as the solution to the housing crisis was given much more visibility and credence than it had previously enjoyed. And while the Workers’ Party failed to take a seat (by a little less than 50 votes) this near miss for a quite radical and explicitly socialist message demonstrates in fact the viability of the approach. If only slightly more effort had been invested, success surely could have been achieved.

Electoralism is dangerous and the pressures to reconcile to the status quo are very real. Failure in elections is painful for active party members and especially for candidates. In addition, the access to funds, a thing always so elusive to the socialist party, provides a strong incentive to growing the number of votes. Both of these factors push parties to move towards the current political economic norm and against suggesting anything too extreme. The promotion of candidates can lead to individuals who, incentivised towards popularity, obtain power which can not easily be checked by party structures. It’s also possible to have a very shallow party movement who have only a small political machine and no real organisational depth, while enjoying some electoral success.

And when socialism appears on the horizon of a democracy, one can be assured that the US will step in to divert the course.

These criticisms while real, cannot change the fact that the alternative approaches do not even yield significant dangers of failure because they fall so far short of success.

Revolutionary Reality

The last generation of political activists can be excused for believing that the revolutionary horizon was removed entirely. It was after all, the era of the end of history. However, the end of history has ended. Revolutionary conditions are likely to assert themselves with very high probability in the coming period, not least of which is the reality of a rapidly changing climate, which potentially leads to the of a kind of terminal crisis of capitalism which Luxemburg had only considered theoretical. Coupled with this is an increasingly unstable geopolitical situation, which while currently mono-polar, may not remain for too many more decades.

Far from meaning we should eschew activity in the electoral arena, instead it presents the possibility of popularising revolutionary aims through the ballot box once again. Bold initiatives are needed in bold times. Putting forward an ambitious but realisable programme of transition to socialism may have seemed pie in the sky in 1995, but in 2025 it’s the only thing capable of saving us from climate catastrophe, making non-revolutionary measures the outrageous ones.

Conclusion

A party with the aim of socialism and deep roots in the working class simply does not yet exist in Ireland, however, history demonstrates that it is possible for one to exist. History can also give us very important clues about which strategies can be pursued with any hope of success.

The situation in Ireland is perhaps more dire than people have given it credit. Sinn Féin will prove to be ultimately a pointless enterprise, having no genuine dedication to socialism. Indeed apart from a vague interest in some sort of republican sentimentalism, they hardly have any ideology at all, and could transform into Fianna Fáil quite readily.

And aside from this we have Solidarity who is currently in the midst of a 3 way split, people Before Profit whose core values are something about cannabis and protecting people from inheritance tax, we have Independents for Change, a group which actually contains the lack of commitment to being a genuine party in its very name, and then a range of very small socialist, communist and republican groups, including Éirígí, the Workers’ Party, The Communist Party and others.

A commitment to creating a genuine socialist party of the working class, in more than just name, is then a very daunting task in the current climate. It will require heroic efforts of courage and force of will to discover the process for assembling and fusing those forces which are present and gathering up those which can be encouraged. Yet it is a task which we desperately need to undertake if we are to have a future. Continuing down proven failed paths, or shying away from proven ones because they feel too uncomfortable or difficult, betrays the working class of Ireland as a whole.

Gavin is International Secretary of the Workers’ Party.