Trotskyism and the Transitional Programme are a political and theoretical dead-end argues Cornelis van Vliet

As communists it is our task to point to the way forward for the workers movement. Through a critical analysis of society we arrive at a vision of where we should go strategically and tactically. In this search for the correct strategical outlook it is crucial that we look critically at the theorists of the past, since their ideas and arguments (often in a twisted way) still play a large role today in the current revolutionary left.

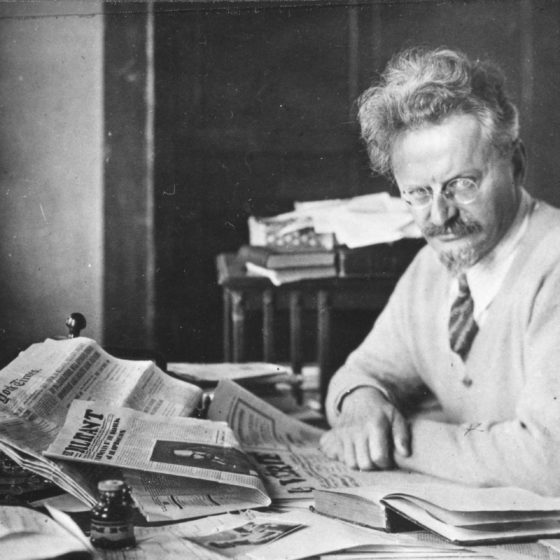

An example of such a theorist is Leon Trotsky. As a Bolshevik, a writer and a revolutionary Trotsky has had a large impact on the communist movement in Russia and elsewhere. Various contemporary organizations in my country, the Netherlands, still adhere to “Trotskyism”; like the International Socialists, Revolution (IMT section) and Socialist Alternative.

Although the Trotskyist movement has, since its inception, had a hard time gaining political relevance its political tradition has left us with a wide variety of theoretical works. Trotsky himself wrote a large collection of inspiring works, like his critique of the USSR and its foreign policy or his analysis of Fascism.

One of his most influential texts is the “Transitional Programme”. In this text Trotsky sets out a vision for how communists should construct their programme fitted to the context of the time period Trotsky lived in. This text to this day still has a lot of influence on Trotskyist organizations and the rest of the revolutionary left. My goal with this article is to explain what the text is all about, what is wrong with the concept of the Transitional Programme and show how this still has a negative influence on the current radical (Trotskyist) left.

Capitalism in decline?

The text about the Transitional Programme was written in the year of 1938. Through the hard work of Trotsky and his co-thinkers a small but not insignificant Trotskyist movement had been built up in the West who kept the fight against Stalin(ism) and capitalism going. In the meantime, most of the workers movement was dominated by reformist or Stalinist parties.

Trotsky starts his text with an analysis of the current political situation. Capitalism is assumed to be in a state of decay and will soon come to an end. A new world war is coming, which will be the death of the existing political and economic powers. Socialism, Trotsky says, is not only on the agenda, but a necessity which arises out of the feeble state of the existing order. There is a political irrelevance of Trotskyists, but an existential crisis of capitalism and thus a political relevance of socialism.

It is this paradox which moves Trotsky to argue for a specific approach to programmatic strategy. First, he breaks with the idea of the “minimum-maximum” program, which was the programmatic structure both the Bolsheviks and the old (Marxist) Social Democracy used. Simply put; the minimum part is the demands which can be met under capitalism and provide the basis for the dictatorship of the proletariat, while the maximum part is socialism (and eventually communism).

Instead of this minimum-maximum structure Trotsky argues for a revolutionary alternative. The fall of capitalism and the urgency of socialism is here, so a programmatic strategy should focus on pushing capitalism over the edge.

In the text, Trotsky makes a distinction between partial and transitional demands. Partial demands are mostly economic strike demands, like “wage-rises indexed for inflation”, “guaranteed full employment”, which can be used in the struggle of working people and don’t really go beyond existing class consciousness.

While usually these demands would not be considered very radical, Trotsky argues that due to the current state of “capitalism in decline” partial demands become revolutionary demands. Capitalism in its current state can’t deliver the goods (not even wage rises or full employment) so by demanding the “impossible” we get the transitional demands. The transitional part of the programme is essentially the dictatorship of the proletariat and socialism, established through worker control and expropriation.

In contrast to the old minimum-maximum program, Trotsky thus breaks with the concept of “revolutionary patience”. Communists should not patiently build a movement which wins the majority of people for socialism, because socialism is supposedly already on the agenda. The reality of a capitalism in decline means that the necessity of socialism becomes clearer by the day. By organising ordinary people for demands capitalism can’t deliver, they will realize that the system is broken and spontaneously accept the necessity of Soviet power and worker control. The system can’t deliver the demands, so people will realise that they have to end the system.

This entails that Trotskyists, despite their political irrelevance, can still win relevance. By organising people on these partial demands the consciousness of ordinary people will spontaneously move towards the necessity of socialism. The eventual confrontation with a decaying capitalism is the moment when the small, theoretically pure Trotskyist groups can win influence. Due to the fact that they are not plagued by theoretical “dead-ends” like Social Democracy or Stalinism, the Trotskyists will come up on top.

Theoretical decline

There are many problems with Trotsky’s concept of the Transitional Programme and his accompanied political analysis. Let’s start with his historical predictions.

Trotsky was murdered in 1940, so he didn’t live to see his predictions play out. Contrary to what he expected, the Second World War was not the death of capitalism and the system came out stronger as ever. This means that Trotsky’s analysis assumes capitalism to be a lot less resilient than it really is, considering the fact that it is still the dominant economic system today.

Next to his wrong predictions, Trotsky’s text also has severe illusions in spontaneity and the organic growth of class consciousness. There is no reason why the struggle for better living standards will automatically translate into the masses becoming revolutionary socialists. Such class consciousness doesn’t merely arise organically, but primarily comes about through the patient organising work of communists who raise class consciousness and spread revolutionary ideas among the masses. A political programme which assumes the necessity of socialism will automatically arise from simple “bread and butter” demands will never get any further than bread and butter. Even if such a struggle for bread and butter would translate into a general political and economic crisis, this in no way would necessarily entail the proletariat taking power.

This is because the forming of worker councils and a general strike are by definition economic means of protest, while what we need is a political solution. When the partial demands and strike tactics of the Trotskyists push capitalism over the edge, it will be the most politically organized groups which will take over. The idea that a small vanguard party, without any mass basis in the working class, will be able to arise victorious out of a revolutionary crisis is laughable. In the search for a political solution society will solve the crisis either by the most politically organised group taking power or by the restoration of the old order.

A good example to illustrate this is the Egyptian Revolution. Despite talk of progressive change it was not the left which took power but the Muslim Brotherhood. Because they were the best organised political movement, with its own institutions and deep roots in sections of the Egyptian population, the Brotherhood could fill the political vacuum. When they were kicked out of power it was the army that did it; the old armed order.

The problem with the Transitional Programme is thus that it pleads an illusionary shortcut to revolution. Instead of building a Communist Party, rooted in the working class, the masses are supposed to be tricked into constructing socialism. First, the working class will be guided through the economic struggle by the Trotskyist vanguard, after which they will realize the system is broken, and automatically set upon the path to form strike committees (and eventually soviets). This path to revolution more resembles the tactics of Louis Blanqui, who Marx ruthlessly criticized for arguing that socialism could be delivered by the action of a small enlightened political minority.

An accompanied effect of this economistic path that the Transitional Programme advocates is that the importance of a political programme is practically ignored. For Marxists it is the utmost necessity to have a programme, which sets out our strategy, our minimum and maximum demands and our analysis of society. Such a programme provides a clear political basis on which we can win people over to our party, while also providing a way for the rank and file of the organisation to exert democratic and political control over the leadership. With the Transitional Programme, Trotsky reduces the question of political power to a mere winning of partial, economic demands which somehow will automatically translate into socialism. This means that there is no realistic connection between the partial demands and the transitional ones; how do we truly get from the one to the other? Interestingly enough, this faith in the organic power of partial demands strongly resembles the reformist Dutch Socialist Party, which often argues that the struggle for bread and butter issues is itself the road to socialism.

I would furthermore argue that the failure of Trotsky to provide a realistic link between the partial and transitional demands arises out of his misinterpretation of the concept of the minimum-maximum programme. In his eyes the minimum part of the programme is merely the finishing of the bourgeois revolution and since capitalism is in decline, such a revolution should not be considered progressive. Another interpretation of the minimum part of the programme, which in my eyes is the correct one, is that the minimum demands are the basis for the dictatorship of the proletariat. As a class we need a political solution to take political power, which also means we need to define the conditions on which a Communist Party should and can take power. We also need fighting demands and political positions on questions that are important for our class.

These elements come together in the minimum part of the programme, which is what policies a workers government would carry out, while also describing how such a takeover of power would happen. After the minimum part is carried out the base would be created on which socialism (and eventually communism) can be built; the maximum part. In this way you have a clear connection between your direct political programme (the Dictatorship of the Proletariat) and your end goal (Socialism), instead of a vague relationship between partial and transitional demands.

The last part of Trotsky his Transitional Programme text I would criticise is his fetishism of council democracy. The council system of soviets, built from spontaneous strike committees, is seen as the best way to form a future state. This is understandable considering the fact that Trotsky himself played an important role in the Russian Revolution, which was built on precisely these Soviet council structures.

Contrary to what Trotsky thinks such a solution to the issue of political power is illusionary. These direct-democratic council structures are built in such a way that people need to be permanently politically mobilised to ensure proper democratic control is exercised. When the hype of the revolution dies down, the power within these councils is slowly taken over by the executive committees. We saw in the Russian Revolution how such a dynamic, combined with civil war and militarisation, turned the Soviets into a nasty bureaucracy free from democratic control. In practice only a directly elected body of representatives, which is in (almost) permanent session, can provide a stable basis for the new political order. The alternative we need to prevent bureaucratisation is not a soviet state, but the democratic republic.

The Transitional Programme today

Now that we have an understanding of where the Transitional Programme goes wrong in theory, we can look at Trotskyist praxis. Most examples I give are from the Dutch Trotskyist movement, but I dare to say that they can be applied universally and are recognizable to anyone who has spent some time on the revolutionary left.

First and foremost, most Trotskyist groups have adopted a weird kind of fatalism. Although in the 50’s some Trotskyists rejected Trotsky his prediction that capitalism would soon collapse, most modern groups have held onto it dearly. Most Trotskyist sects are still going on about how a new capitalist crisis, the collapse of the system and a revolutionary crisis are around the corner. In 2013 for instance, the Dutch section of the IMT (Revolution) claimed that capitalism was past its sell-by date and the world revolution was near. That such a breakdown of capitalism has not happened is clearly not a falsification of their views, since they make exactly the same claim in their recent publication on the corona crisis. Such analyses produce an endless repetition of useless dogma’s; the death of capitalism is now finally really here! That reality proves the resilience of capitalism never falsifies their thinking which makes these “Marxist” predictions unscientific and useless.

This brings me to my second point; the effect of the Transitional Programme on strategy. As I said earlier, Trotsky denies the relevance of a minimum-maximum programme, and thereby reduces the question of a programme to a few partial and transitional demands. This plays out in the practice of Trotskyist groups, of which most don’t even have a political programme.

The Dutch section of the IMT and the Dutch Socialist Alternative consider their “programme”, if you can call it that, a few economistic trade union demands. The Dutch International Socialists (our largest Trotskyist organization) doesn’t even have a programme. This means that in practice the political and strategic base of the organisation is whatever the leaders want it to be; a dictatorship of (paid) activist bureaucrats.

The absence of a programme drafted and created by members means that democratic control and discussion over the political guide to action is made more difficult. When a political organisation does not collectively determine their shared strategic outlook and demands the party bureaucracy is free to change course anyway they want. Combine this with a bureaucratic interpretation of democratic centralism and you get a party form where any criticism by members or attempt at democratic control is beaten down by the existing leadership with a few references to Trotsky or other “holy” theoretical texts.

A consequence of this is the constant split, sect culture of the contemporary Trotskyist left. With every political disagreement there is a new split, since there is a lack of a shared political programme which can be amended and critical debate is made impossible.

While in many Trotskyist organizations there is very little time for discussion or democratic procedures, there seems to be plenty of time for other things. Trotskyist groups for instance write weekly or monthly newspapers, which in practice are full of endlessly reproduced dogmas, without producing anything remotely theoretically interesting.

Another important activity for Trotskyist groups is attempting to set up (popular) front groups or opportunistically take over existing social movements. Every new protest wave is used as an excuse to set up front groups or mass-recruit new members. Trotsky’s focus on the importance of partial demands is in this way often used in practice to hide revolutionary politics and focus on leeching off of existing social movements.

The shortcut way to revolution preached by the Transitional Programme is also clear in the way the Dutch IMT looks at building a party. Communists, according to Revolution, should not be busy building a Communist Party or winning the existing workers movement for a communist programme. Their vision is that of the theoretical sect; communist organizations should stay theoretically pure until they can ride the inevitable revolutionary wave (this time well predicted) to leadership over the masses. The consequence of this thinking is dogmatism, sectarianism, and a complete refusal to engage politically with the existing workers movement.

Trotskyist organizations in other countries are not very different. Worldwide the political legacy of Trotsky has been split up into hundreds of competing sects, each waiting for the next revolutionary wave or leeching off of social movements. Larger Trotskyist organizations like Socialist Alternative in the US or People before Profit in Ireland have capitulated to parliamentary coalitionism and the almost uncritical tailing of Social-Democracy.

The answers for us as communists thus do not lie in the theoretical and political dead-end of modern Trotskyism or the Transitional Programme. Our path to socialism cannot be reached through shortcuts to revolution but only through the patient building of a communist organization which has firm roots in the existing workers movement and the working class. For this we need a minimum-maximum programme, which provides us with a clear vision of political and social demands, strategy and analysis. The path to a resilient political programme and a Communist Party starts with a critical evaluation of the dogmas of the past!