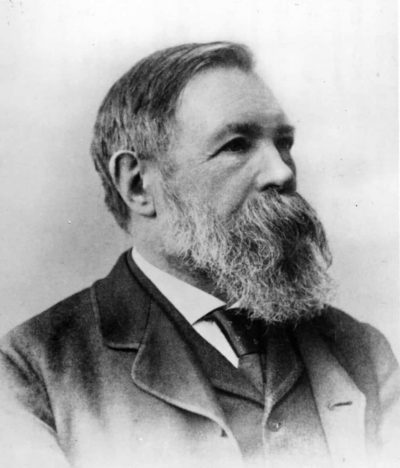

Friedrich Engels’, the co-inventor of Marxism, was born 200 years ago, on 28th November, 1820.

As lives go, Engels lived a full one: raised a devout Christian he became a pre-eminent atheistic philosopher; from a family loyal to the Prussian monarchy, he engaged in military rebellion against it. A proud German patriot, his revolutionary activity saw him forced into a life of exile by Prussian state; obliged to work as company manager for the family firm, his entire political career was devoted to the cause of the working class; from Hegelian dabbler to committed materialist, his political life alone was crammed full to the brim.

His life and achievements, significant in his own day, have continued — and will continue for as long as society is divided into classes — to inspire examination of how society functions and, just as importantly, how it can be changed.

Traditionally, and by his own admission, seen as playing second fiddle to Karl Marx, Engels in fact is the source of some of the key ideas in Marxism: the necessity to abolish private property, the identification of the bourgeoisie as the ruling class and working class as the agent of communism, the economic foundations of the family, the basic political strategy of Marxism, and, not least, historical materialism itself.

If Marx ultimately delved deeper into the operational detail of the capitalist mode of production, this was in no little way dependent on not only Engels’ practical support and intellectual companionship but also Engels’ illumination of the fundamental point upon which to build, namely the study of political economy of capitalism itself and, from there, the active role of the proletariat and the consequent concept of the class struggle.

For Engels, recognising the inherently alienating effects of having to sell one’s labour for wages, came to communism quite independently of Marx. Engels saw as early as 1844 in his Principles of Communism, that private property in the means of production – factories, land, machines and these days, patents – necessarily implied a mass of dispossessed – the proletariat – who, owning nothing but the clothes on their back, could live only by selling their ability to work for the owners of private property.

The influence of his early masterpiece, The Conditions of the English Working Class, whose penetrating insights were made possible by his Irish partner Mary Burns’ facilitating his contact with Manchester workers, marked a leap forward in the practical knowledge of the actual lives of working people.

If previously the philosophers’ reasoning about the proletariat had something of an ethereal quality, this book brought it firmly back to the dirt and grit of the capitalist urban landscape.

From this came an unflinching focus on the proletariat as the agents capable of building a socialist society.

Only they had the material interest and, thanks to pressure from capitalism that stripped them of their antiquated culture and forced them to organise into co-ops, trade unions, and ultimately, a political party, the capability of supplanting the bourgeoisie.

In the period before the explosion of 1848 Engels and Marx, both separately and together, developed the foundations of their distinctive political philosophy, i.e. a rejection of ahistorical analysis. The world, even the social and intellectual world, was no longer to be understood in terms of spirit or ideas, but rather as stages in the development of real things: matter, bodies, groups and, critically, how these things came to be.

Ideas themselves were layered on top of, and dependent on, the real world to run (whether brains or paper and ink) and, logically, for the financial resources to deploy them. With the preponderance of resources belonging to the ruling class it followed that their ideas, ideas which reinforced their social position, would dominate society.

Rather than fruitlessly take on that intellectual edifice directly — as seemed to be the approach of their socialist predecessors — Marx and Engels realised that only a movement of comparable social strength could generate the necessary material resources to prevail, not only socially but intellectually.

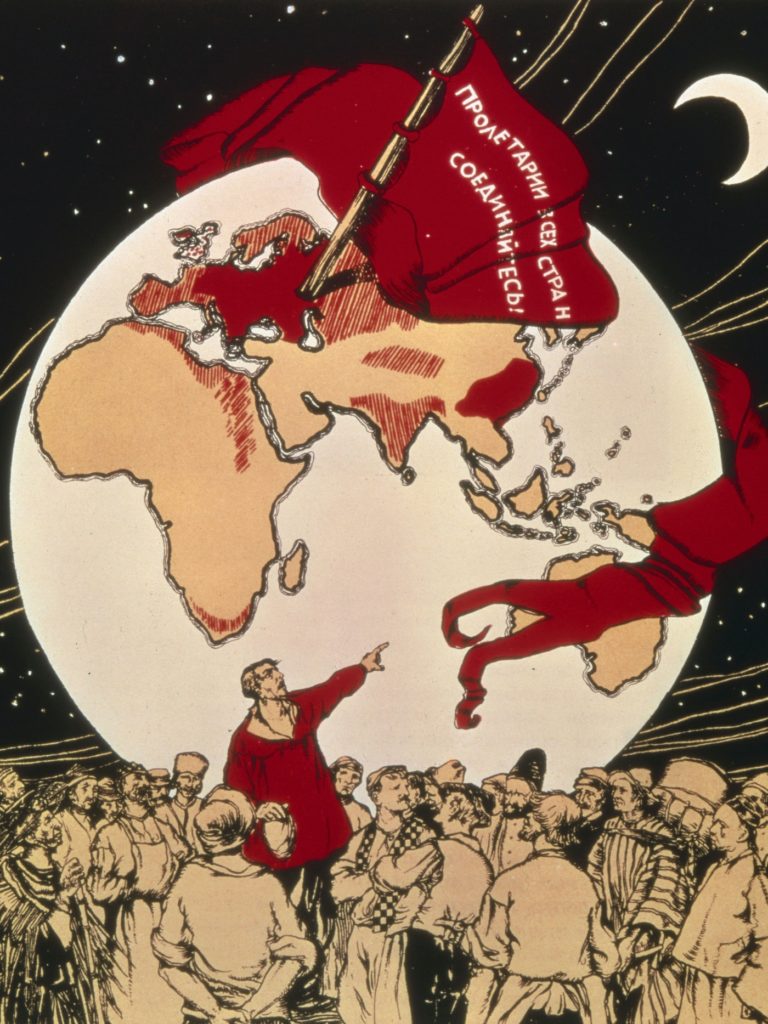

In this lies their greatest contribution to political organising, the realisation that only by merging with the labour movement could communists influence a movement strong enough to combat the immense resources deployed by the ruling class.

There were socialists before Engels — indeed advocates for communism can be traced back to antiquity — with a fresh crop arising in response to the Industrial Revolution which had been spreading from England since the late 18th century.

And there were also longstanding workers’ movements; the ancient guilds, evolving under the pressure of capitalist production towards trade unionism, were still extant and beginning to expand following the advent of steam and loosening of the post-napoleonic era repression.

Engels, however, brought something new: the merger of socialist intellectuals and the proletarian workers’ movement. No longer merely the continental intellectual schooled in German philosophy and French socialism, he was influenced by the working class movement in England, Chartism, which struggled for political reform and threatened revolution.

As Karl Kautsky later summarised Engels’ breakthrough, both the modern labour movement and socialism emerged in response to industrial capitalism, but they had emerged *separately*: the workers movement primarily from the proletariat, socialism from the bourgeois strata. Both had their champions: Cabet, Saint-Simon, Weitling, the English Chartists to take a few. What Engels was first to do was to proclaim the necessity for the merger of socialism with the workers’ movement.

This is often a tough pill for socialists to swallow given the often relatively conservative disposition of the trade unions. At times – as with the passive attitude of English workers towards imperialism later in the 19th century – Engels was none too enthusiastic himself. But reality dictated that it was the only way for both wings — trade unionists and socialists — to exert influence, most especially in the advanced capitalist countries, and Engels relentlessly pushed for socialists to take part in, learn from, and educate the trade unions.

Only trade unions could provide a long-term mass base for a nationwide political party. The deep insight of this view is made manifest by the relative success of the socialist-labour movement whenever the two strands have unified, from pre-war German Social Democracy to the various large Communist Parties.

And when the merger is dissolved, i.e., when socialists return to being purist parties devoid of popular following, or when the trade unions exclude socialists and evolve into being just another lobby group, both wings are weakened terribly.

In the 1840s, when Engels first hit upon the insight, the merger itself was still some way into the future. But Engels, even if he was a visionary, was no utopian. The immediate task for European revolutionaries in the mid-19th century was to overthrow the absolutist regimes that smothered the continent, closing off any arena for dissident political thought and quite often simply prohibiting the idea that states should have constitutions.

But the growing reach of capitalist production increased the social power of the bourgeoisie, inevitably placing them in opposition to reigning aristocratic classes. Combined with a growing proletariat and distressed petty bourgeoisie the stage was set for a continental replay of the French Revolution of 1789 that had smashed the power of the aristocracy there.

The second round came in 1848, with the overthrow of the July monarchy in Paris echoing across the continent and threatening the crowns in Vienna and Berlin before order was finally restored at the point of the Tsar’s bayonets. Russia thereafter loomed large in the calculations of both Marx and Engels as the enemy of democracy.

Engels realised that if the working class was to liberate itself – and thereby humanity as a whole – it could only do so under conditions of democracy and liberty, where it had the space to organise itself. There being no such freedom for any class in the absolutist regimes of mid-19th century Europe, the proletariat had a common interest in working with all democratic forces to overthrow the tyrants. As such, he was a leading voice promoting the establishment of democracy as the immediate goal and was quite prepared to work with other progressive forces to achieve it.

When the predicted democratic revolution finally broke out he returned from exile to Germany to participate as an organiser, journalist, and soldier. Military defeat, however, beckoned and he was forced to retreat to England where the spectre of poverty for both himself and Marx forced him, much to his chagrin, to return to the family business to support their joint political endeavour.

By 1850, with the revolutionary wave on the continent crushed by the forces of reaction, both Marx and Engels had settled down for the long haul and focussed on developing the critique of the capitalist mode of production. As Marx embarked on his epic focus on unveiling the inner dynamic of capitalism Engels combined working the day job with journalism, editing Marx, and, once he managed to retire early, recommit to writing, with highly influential works defending his and Marx’s philosophy (the Anti–Duhring) and his treatise On the Origins of Private Property and the Family being most notable, the latter still used as a jumping off point for understanding how relations between the sexes came to be.

But his field of interest was enormous, from editing Volumes II and III of Capital to historical writings on subjects ranging from the Hegelian influence earlier in the century to the peasant wars in 16th century Germany, philosophical ruminations on nature, and an insightful interpretation of the social origins of early Christianity, all which inspired treatments from the following generations of Marxists.

Engels’ works brim with insight. Even where he is wrong or outdated, there is usually insight to be gained, albeit the sheer forthrightnesses borders occasionally on outrageous, as with his youthful predictions for the Slavs (an non-historic people destined for oblivion) or the Irish (“The Irishman is a carefree, cheerful, potato-eating child of nature”).

The German patriotism underlying that initial dismissal of Slavs was real even as he hated the Prussian state’s reactionary authoritarianism. For Engels, the ruling class, by excluding the proletariat from the political life of the country, could no longer claim to be bearers of the national interest. That baton now fell to the labour movement and he was quite prepared for it to support the defence of the country should it be needed to prevent it being conquered by a reactionary power like Tsarist Russia. He was no chauvinist however and fully accepted the right of the labour movement in other countries to defend themselves against aggressive Prussian predations if necessary.

His final years from the 1880s to his death in 1895 saw him act as a sort of international consultant to a myriad of rising Social Democratic parties dispensing advice through an incessant stream of correspondence with socialists across Europe. His German patriotism was no barrier to international solidarity so advice was dispensed to parties from Portugal to Poland. In this he remained true to his youthful conception of the merger between the labour movement and socialism, albeit modified by a less Jacobin disposition than he and Marx had worn in their own era of revolutionary activity back in the 1840s.

But only relatively so. He held no illusions about the despotic nature of the continental regimes (in contrast to England) and that they would need to be overthrown by force. But that force could not be arbitrarily conjured up. To attempt an uprising at the wrong time would leave the movement open to being destroyed by the state.

Rather Engels argued that it had to continue building its by now massive support until it was subject to an aggressive attack by the state; then from a position of democratic legitimacy it would have the widespread social backing necessary to overthrow the aristocratic regime and institute a democratic republic in which socialism could be built. He was not interested in electoralism per se but in electoralism as part of building a popular movement capable of revolutionary action on a wide scale rather than the conspiratorial groups that had blossomed in his youth and which periodically reappear.

Engels died in 1895, just as the Social Democratic movement was taking over in a big way all over Europe. The story of that movement and its successors in the post-war Communist Parties is full of ups and downs but the role of Friedrich Engels in bequeathing their fundamental political orientation and his immense contribution towards their intellectual foundations ensures he will be long remembered as one of the founders, perhaps the key one, of the most influential movement of the last 200 years: the socialist-labour movement.

James O’Brien is a member of the Workers’ Party Ard Comhairle.